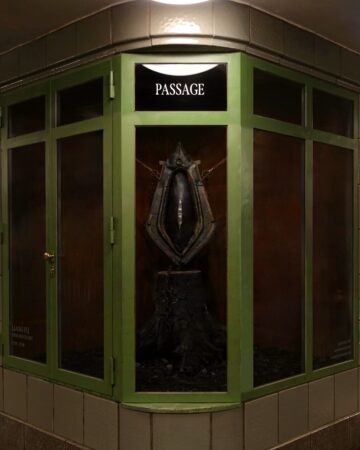

“SPINE BOUNDARY”: IN CONVERSATION WITH LIANG FU (FEAT. PASSAGE)

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…

Sex, Gender and Painting

The studio is located on the lower level of Quartier 205 on Friedrichstraße 69, Berlin-Mitte. The front glass facade is draped with black molton, shielding the interior from unwanted glances. Entry is granted to those on the list. You could find the same queue outside of Berghain. Lots of black, mesh, lacquer, leather, but most of all: skin. Behind the opaque curtain, a small studio space with a kitchen opens up. Massive lightboxes are installed just below the ceiling for interaction. They come to life through arm movements and proximity to the body. Some time passes before the lightboxes are deinstalled, in a brief interlude, making way for the evening’s performative segment. Jonathan Apelbaum, the artist and central figure of Studio Apelbaum, pragmatically tempers expectations: “It’s a showcase, a process, nothing conclusive.” Electronic music, dark and dissonant, begins and grows more rhythmic. A performer dances in jerky motions. Like gathering around a fire, semi-naked individuals – their few covered body parts also draped in black clothing – sit in the shadows, merging with the surroundings. The room is packed. Every square meter is occupied, everyone seated on the floor. Due to the warmth, people perspire into the room, everything blends into a dense fog of scent, a homogenous heap of unity. After the performance: applause, congratulations, warm words, lots of affection. Sven Marquardt resists the label “bouncer,” preferring “audience curator” as his role description for the techno temple Berghain. The same following of this queer rave sect constitutes the community of Studio Apelbaum. It embodies an underlying shift characterizing contemporary art. And what art historian and cultural scientist Wolfgang Ullrich denotes as post-autonomous art.

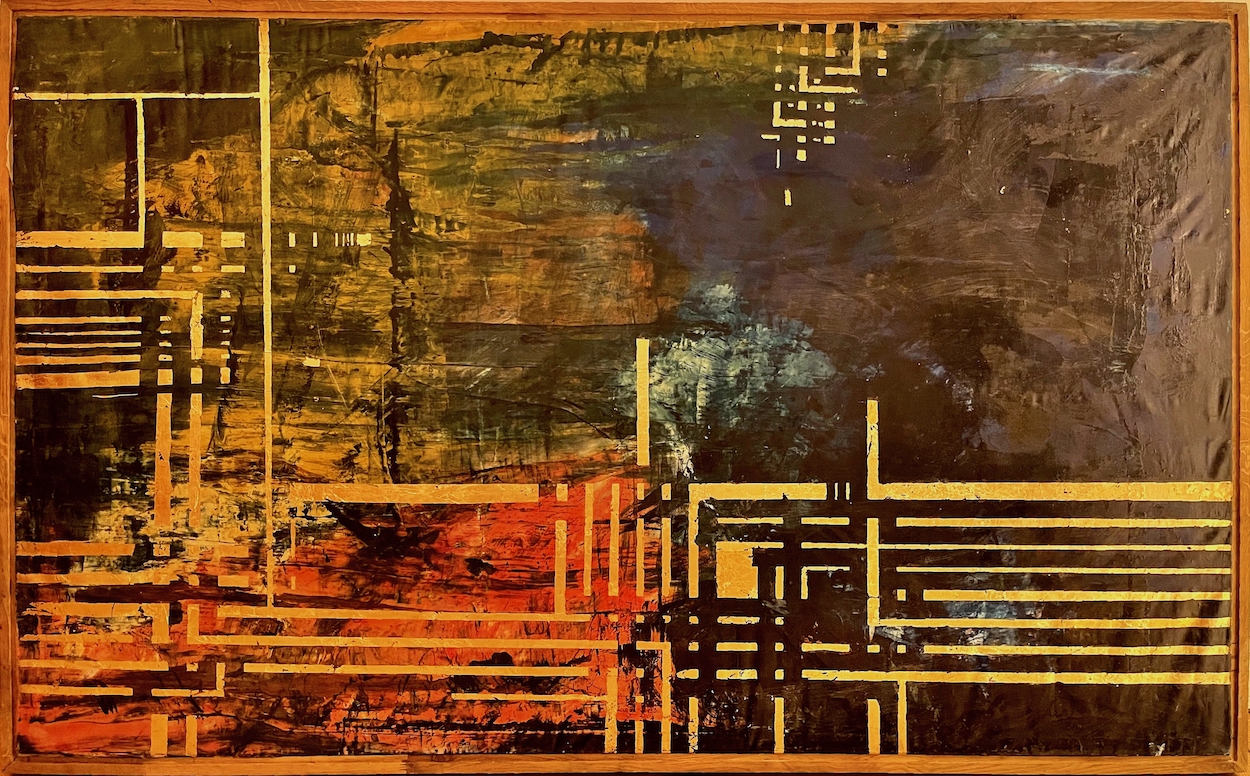

Jonathan Apelbaum’s art does not happen in a white cube. This doesn’t mean his art wouldn’t be presentable in a gallery space. On the contrary: The exhibition “The Queer Last Supper” at Galerie Samuelis Baumgarte in Bielefeld demonstrates that the animated, large-format paintings – Apelbaum calls them “cognitive paintings” – fit wonderfully between white walls. Apelbaum’s art not happening in a white cube rather refers to its genesis. The paintings, as recently exhibited in that comprehensive solo show in Bielefeld, blend abstract and figurative elements. In daylight, without backlighting, they appear like excessive battles of material. Strips of gold leaf, thickly applied paint, brightly glowing tones – an ode to the opulence of painting. For the series at Galerie Samuelis Baumgarte, Apelbaum interviewed other artists, creatives, activists and friends. Initial acquaintances from nights spent partying and sharing moments of club culture. They are all currently in transition, in a liminal state of identity. Apelbaum processed the recordings of the interviews in collaboration with Davide Serpico into sound collages, complementing the Bielefeld gallery space alongside the paintings. The interviewees accompany the exhibition throughout. Once activated, the lightboxes transform the previously visible abstractions into figurative apparitions. Contours become visible, sometimes curved, sometimes etched. Gestural work on the canvas is evident in these pieces. Their creation process, the interviews, the translation of narratives onto canvas, all belong to the work as much as the interactive moment with the viewers of the painting-lightbox. The “cognitive paintings.” They bear the names of their muses: “Matilde,” “Julie,” “Hubertus.” Being part of the process means belonging to the community, sharing the same values and moral principles. The paintings are representations of collective events, memories of communal experiences, often orgies. Wolfgang Ullrich describes the transformation process into what he refers to as “Realien” (artefacts) in his latest book “Die Kunst nach dem Ende ihrer Autonomie” (Art After the End of Its Autonomy) as follows: “Then, instead of an autonomous work of art, there is an object that is a well-recognizable, globally traded brand product, perhaps addressing serious – political, social, ecological, emotional – themes or unleashing activist energies, but not only existing as a single piece in an exhibition space, but available in many variants and versions […].” Apelbaum’s “cognitive paintings” literally radiate beyond the gallery space, the streaming crowds of curated community queueing up before the club-like entrance, at least visually akin to Roman Ondák’s performance “Good Feelings in Good Times” from 2007.

Although it seems intuitive that the project around Studio Apelbaum grew out of the community, the artist, born in Glasgow in 1992, asserts something different. “In the beginning was the painting,” Apelbaum confidently claims. Raised in the Parisian banlieues as the eldest son of French-Algerian-Polish parents, Apelbaum initially studied mechanical engineering and vehicle technology at the prestigious ETH Zurich and later worked as a project manager at Siemens, Bombardier, and other industry giants. Since 2021, Apelbaum has been institutionalizing his artistic interest in the form of associations, structures, and collaborations, ultimately: with the studio at Friedrichstraße 69. Not only did Apelbaum’s initial interest grow out of painting, but throughout his youth, the king’s discipline of flatware accompanied him as a means of artistic expression. “The community wouldn’t function without the pictures,” Apelbaum knows. They are at the beginning and the end: from the collective conceptualization of the pictures, the exhibition ultimately arises. Here, the same community that founded the origin of the pictures becomes visible. Only in between, they must pass through the creating hands of the artist.

Additionally, Apelbaum’s affinity for technology and innovation is evident. With the “cognitive paintings” and the soundscapes, Studio Apelbaum aligns itself with a longstanding tradition. Historically, painting has been a means of emancipatory or reformist endeavors. Not only has the theme of sexual, physical as well as intellectual liberation been repeatedly the subject of art history – for instance, with Rainer Fetting, Lorenza Böttner, Andy Warhol, Francis Bacon, Robert Mapplethorpe, Jean Cocteau, Georgia O’Keeffe, or Gustave Courbet – but also the affinity for new, technical achievements is deeply programmed into the history of art, especially painting. Historical examples such as the Camera Lucida and the Camera Obscura were revolutionary tools that opened new ways of visualization for artists. Even today, it’s always worth revisiting David Hockney’s “Secrets of the Old Masters” to marvel at the progressiveness and openness of the technical means of that era.

The use of lightboxes for Apelbaum’s paintings, on the other hand, recalls the use of new technologies for the analysis and interpretation of classic paintings. Consider, for example, the exhibition of Auguste Renoir’s “The Couple” in 2013 in Cologne or Rembrandt’s “Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife,” at the Berlin Gemäldegalerie in 2007. These examples were exhibited not just as mere paintings but were “illuminated” in the truest sense of the word, through special framing arrangements. There are visualizations of prior X-ray examinations to reveal previously “hidden” or overpainted stories of the paintings. This practice reflects how painting, or engagement with it, is an expression of dealing with the latest technologies. Jonathan Apelbaum continues and expands this tradition.

Yet, the secret lies not only in the painting, but also in the structure. Apelbaum himself describes the organizational complex as a challenge to the status quo. The goal: The liberation of the individual from societal constraints. A goal also pursued by generations of artists before him. Likewise, with the motivation to halt a collective coarsening, desensitization, alienation from nature, and dehumanization. Often also through sexual liberation, as Apelbaum emphasizes. Think of Monte Verità in Tessin, Otto Muehl’s commune (“Action Analytical Organization”), or the artist colony Worpswede. However, where Apelbaum decidedly differs from his predecessors: On the one hand, Apelbaum strives for queer liberation with the studio; on the other hand, the studio follows a clearly hierarchical, yet transparent organizational structure. His ideal image: “La Decadence de la Rome.”

With this intertwining of various elements, the Berlin artist strikes at the heart of current developments and needs. Not only the handling of post-autonomous art, but also the sexualization or at least eroticization of the so-called art world is now an intrusive phenomenon. Just in November 2023, Monopol editor-in-chief Elke Buhr, together with Sebastian Frenzel, wrote an article titled “Schmerz, lass nach” (Pain, let go) about the convergence of body, erotica, BDSM, and institutional art experience: “Ultra-tight pieces in shiny leather or latex, killer high heels, harnesses for him and her, wet-look corsets on naked skin: In the past, this was the dress code for the bedroom, for “Fifty Shades of Grey” reenactments, and for the queue in front of Berghain. Today, teenagers drop it into their shopping cart. At art vernissages, meanwhile, the discerning audience enjoys professional pole dancing.”

This phenomenon is most evident in the handling of the communal as an event, especially in the context of performance. Since the second half of the 20th century, performance art has gained relevance, with the ephemeral, the body, and immediate experience traditionally at the forefront. Erika Fischer-Lichte (theory) and Anne Imhof or Angélica Liddell (practice) demonstrate how the event of performance draws from the essence of the interpersonal.

At Studio Apelbaum, however, hybrid events are created from performances, dinners, installations, concerts, exhibitions, and experiments that sometimes culminate in raves and orgies. The community is an integral part of the studio, opening up not only an artistic but also an organizational space. The queer community is both the place and the subject of the emerging works, with subjects and objects being superseded as categories. Apelbaum intertwines biographies and narratives of queer individuals into his art, as in the exhibition “The Last Queer Supper,” for which people in transition were photographed and their stories literally “inscribed” onto their bodies. These portraits became the basis for the paintings.

“The strictly guarded boundary between those who create art and those who receive it becomes […] permeable, perhaps even obsolete. Insofar as reception turns into consumption or activism (or both at the same time), the artefacts (“Realien”) of works become tools.” Wolfgang Ullrich precisely put together how the traditional separation between artists and recipients is blurring, perhaps even disappearing. (Post-autonomous) Art no longer serves only for effect, enjoyment, or sonification. It rather takes on the role of an entity that brings together creatives as well as mechanical engineers, at one table. And thrives in something special.