#PASSION: HOW TO HAVE BETTER SEX – IN CONVERSATION WITH SEXOLOGIST CHANTELLE OTTEN

According to a survey by dating platform Parship in 2023, only every second person is…

Interview by Benjamin Schiffer

The image captures a man, facing away from the camera. He is standing on a large, rock outcrop, amid autumnal woodland at the base of a tall, powerful waterfall, one leg bent slightly in front of himself.

The camera holds its position for a while, as cascades of foaming white water crash with violence into the pool at the very bottom of the falls, creating whorls and vortexes of evident power. For a moment, we are invited to be hypnotized by the rhythms of the water, to consider the spectacle as the man in the frame may be considering it. All the while, the constant flow of water creates an illusion of permanence through its unrelenting movement and flux. You never, as the saying goes, step in the same river twice.

In the next scene, the man faces the camera, explaining that this waterfall was his favorite place to come as a child. He is elderly, with an almost bald head, pronounced facial features, and searching eyes set deeply within his head, behind wrinkled and slightly drooping eyelids. I believe, he tells us, that we all have a landscape of the soul. This waterfall is the landscape of mine. The interviewer, standing out of shot behind the camera, asks where the waterfall comes from, where the river’s source is to be found. The man says that he doesn’t know. He never ventured to the top of the falls and beyond, never followed the river to the source. He says that he does not want to find out.

The scenes described here are taken from a new documentary entitled Werner Herzog: Radical Dreamer, about the life and work of the famed German filmmaker. The man at the waterfall is, of course, Herzog himself. Now 81, Herzog is perhaps the most well-known living German filmmaker, having directed more than 60 feature films and documentaries (though he does not like to distinguish between the two). In the English-speaking world, Herzog is above all a recognizable voice. His distinctive, hyperbolic yet unadorned use of the English language, not to mention his unique Bavarian accent, have garnered him many fans, alongside plentiful cameos and voiceover roles in series and films as varied as The Mandalorian and The Simpsons.

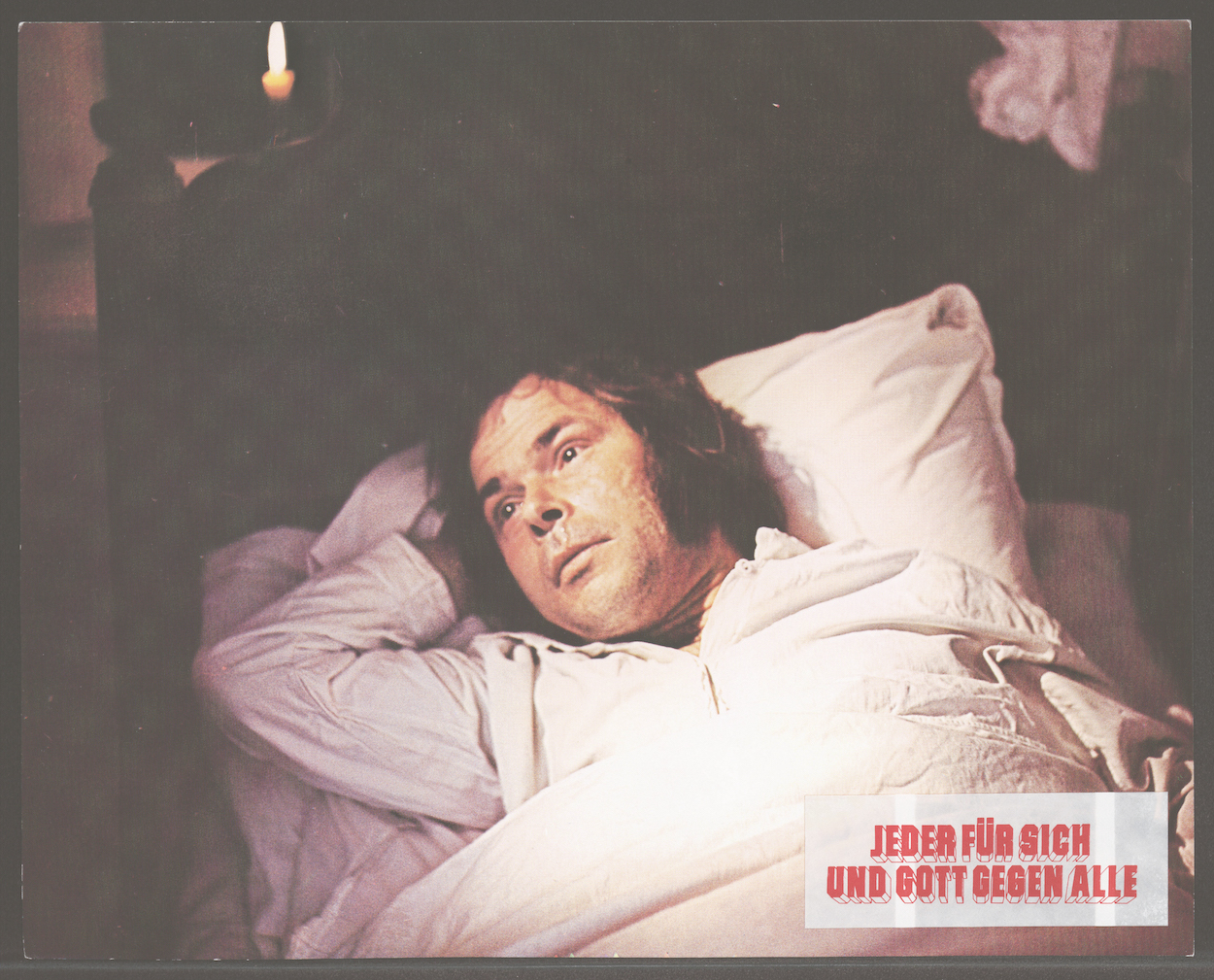

Today, if he is known for any of his films, it is likely to be his documentaries, of which 2005’s Grizzly Man, the film that garnered him widespread recognition and acclaim in the United States beyond cinephile circles, is perhaps the most well-known. However, Herzog made his first film, Signs of Life, in 1968. Alongside Werner Rainer Fassbinder, Wim Wenders and Volker Schlöndorff, he was at the vanguard of the New German Cinema movement of the 1960s and 70s, and many of his most enduring works – both documentary and fiction – were made in that time. Early in his career, Herzog had a more or less permanent fixation on obsessive, driven characters, explored particularly through films such as Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo. These characters have been a feature of his cinema ever since; whether real individuals or fictional characters based upon them, Herzogian protagonists usually share an unshakeable belief in the importance and necessity of their own ambitions. Many have pointed out that they are also, usually, a cipher for Herzog himself.

Though his films have taken him to some of the wildest reaches of the globe, from Antarctica to the depths of the Amazon Rainforest and into the Sahara Desert, like some other great directors (for instance, Yasujirō Ozu), in many ways, Herzog makes the same film each time he picks up a camera. Across a wild diversity of time, space and subject, he searches for the same stories, the same characters, all of whom are driven by something within them to take on things that few others would contemplate. He is attracted above all to the extremities of human experience, human desire and human folly.

Herzog is a gifted raconteur, with a talent for self-mythologization and the creation of mystique. There are so many scarcely-believable anecdotes about him that it is difficult to keep track of them all. Who else could possibly have been shot while recording an interview for British television, cooked and eaten an entire shoe, or have – allegedly – directed a leading actor while pointing a loaded gun at him? If nothing else, the man is acutely aware of the potency of his brand. Werner Herzog: Radical Dreamer demonstrates that, despite his proclivity for reliably droll, pessimistic statements and affected, deadpan persona, Herzog is an intensely private man. The documentary is a sensitive and sympathetic, though undoubtedly partial portrait, which gives us little real insight into who Werner Herzog actually is beyond what might be read on Wikipedia. It has the air of an authorized biography, focusing on his filmography and some of the more well-trodden tales from his famously chaotic film shoots, at the expense of asking any probing questions about himself, his worldview, or his filmmaking philosophy. For a portrait of a filmmaker who explicitly positions himself as a thinker, and whose thoughts, musings and theses are at the very heart of all of his films, this is a grave shortcoming.

The closest the film travels toward an understanding of how Herzog thinks about the world is, perhaps, the scene at the waterfall. As ever, Herzog speaks poetically, almost in riddles. The waterfall is located in woodland close to the village of Sachrang in the Bavarian Alps, where Herzog moved along with his family after being bombed out of Munich during World War II. We learn a little, before we arrive at the falls, about the privations of wartime, the hunger that the family endured when the weekly rations of bread inevitably ran out early, and the alienation that Herzog, an urban child, felt in this strange, archaic and beautiful landscape. In a particularly touching scene, he visits the building in which he was housed during this period. He peers in through the window, and points to where the kitchen used to be. He says that he does not wish to go inside, wiping a tear from his face. These are not, he says, perhaps a little unconvincingly, tears of emotion.

Born in 1942, Herzog’s childhood years were the years of National Socialism, of Hitler, and the unspeakable horrors perpetrated by Germany during World War II. This was the time that made the man, the darkest hour of Europe’s history. If Herzog is often described as a philosophical pessimist, it might be these life experiences that sowed these seeds. He talks often of the chaotic indifference of the cosmos, of the natural state of murder and death that permeates the natural world and, perhaps, our own drives and desires. The film does not explicitly draw connections between the world of Herzog’s birth and the way he talks about the universe, but it does not have to do so. This was the world as he found it.

We learn that around the same time, during his years in the Alps, Herzog wished to be a ski jumper, the beginning of another of his career obsessions: the capacity for human flight. At least three of his films, The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner, Little Dieter Needs to Fly, and Rescue Dawn, have been about men obsessed with flying in one way or another. In a typically Herzogian turn of phrase, he tells us that it is ‘a great injustice of nature’ that he was not to become an athlete, in the same way that it is an injustice of nature ‘that man does not have wings.’ It is as though he is telling us that the only limits that constrain him are those of biology, and that he is suspicious even of these. His studies of those who have tried to transcend this biology suggest that he, too, believes in that capacity for an emotional transcendence of physical limitation.

This fundamentally hopeful belief, this force of will, stands in contradiction to the pessimism that he so often and eloquently describes, and it is this belief that ultimately holds the key to understanding his worldview. Herzog’s most poignant film, Land of Silence and Darkness, is a documentary about deafblindness, centered on a woman called Fini Straubinger, who became deafblind as a teenager. Herzog is concerned with how such people find meaning and find community when the two most vital means of sensing and interpreting the world around us are impaired. What is perhaps most surprising about the film, is the meaning and community that its subjects are able to find through their own persistence, ingenuity, compassion and mutual aid. It takes a grave subject and creates something touching, and ultimately full of hope.

At the waterfall, Herzog strikes a pose not unlike the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog in Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting. Herzog has a complicated relationship with German Romanticism and has openly bristled when critics have drawn parallels between his work and the 19th century movement. He has said that German Romanticism and German Expressionism are the only two aesthetic schools that anyone outside of Germany can think of when they consider German art. He believes himself indebted to neither, but perhaps in his quest to present himself as truly sui generis, he doth protest too much. There are evident traces of each school’s philosophy to be found throughout this work, forming part of his intellectual and artistic DNA. Herzog has said that his visual language is informed by a desire to express the dreamscapes of his characters, and he has an uncanny and strikingly potent ability to render familiar landscapes eerie, ecstatic, unsettling and full of awe. While this may not be capital-E Expressionism, it is undoubtedly influenced by the expressionistic desire to externalize and visualize deeply-held emotions as well as subconscious desires.

These dreamscapes are also landscapes, and they point toward the importance that Herzog invests in a particular idea of nature, an approach to the natural world not unlike that of the Romantic movement from which he has attempted to distance himself. The opening sequence of Aguirre, the Wrath of God, the film that made his name internationally, demonstrates this idea of the natural world very well. In the scene, we see a group of Spanish conquistadors and their indigenous guides traversing an impossibly steep mountain path through the clouded forests of the Andes, marching down from the high mountains toward the Amazon basin. The visual power of the images is hard to overstate, especially given the film’s minimal budget and chaotic production. The astonishing depth of field captured in the images, and the interaction between the snaking train of human beings and the vastness of the landscape through which they are moving, is a profoundly moving sight. It is as though the viewer is witnessing documentary footage of the actual journey that was made, through some feat of magic, back in the 16th century. The familiar tropes of cinematic landscapes are not present, the framing and composition are at once arresting and disquieting. It feels uncomfortably real.

The monumentality of the natural world, its force and severity, and its indifference to the miniscule people attempting to conquer and subdue it, give the viewer a palpable sense of the awesome power Herzog attributes to nature and the respect he has for its transformative, transcendental potential.

In his filmmaking, he is constantly gesturing towards something close to the Sublime, something that cannot be reached but can be approximated, much like truth itself.

At the same time, these images are also the first indication that the film is a record of and commentary upon its own creation. The sheer novelty and beauty of the shot begs the question of precisely how Herzog was able to capture it. As Aguirre continues, there are many more images that not only beg the question of how, but also why? We see whole rafts of people floating downstream on fast flowing Amazonian rapids, dashed against rocks, traipsing through the densest jungle. Much like the titular character Aguirre, adrift down the Amazon, on a cursed and fateful mission to find a mythical city of gold, we are given a sense of the hardships, the privations and the unbelievable challenges overcome by Herzog to make this film, to the extent that we might reasonably ask: Why on earth did he bother? There is no straightforward answer, but Herzog’s films stand clearly as monuments to obsession: not simply to the obsessions of his characters, but of his own passions, his own drive, his own unceasing will. His films are not simply works of sympathy, but often works of empathy. He is interested, above all, in understanding what it must have been like to be a particular individual in a particular situation, facing an extreme of human experience. To that end, his productions have often mirrored the hardships of the people that he has sought to portray on screen. Consciously or otherwise, he has an interest in creating something under extreme circumstances, in overcoming something gargantuan. In Fitzcarraldo, a steamboat is transported over a mountain to reach the Amazon basin. To film this feat, Herzog recreated the undertaking without special effects, deploying the crew to drag a 320-ton ship up the side of a steep hill.

The frequently troubled productions of Herzog’s films reflect both their subject matter and the personality of their maker, but they also reflect his obsession with obsession itself, his desire to be close to this extremity and observe it intellectually, even as he subjects himself and those around him to the same thing. Herzog frequently collaborated with the infamously volatile (and now disgraced) actor Klaus Kinski on many of his most famous films, including both Aguirre and Fitzcarraldo. Kinski’s rage and violent behavior on Herzog’s sets has become legendary, with extensive footage and sound recordings of his instability. In the documentary, Herzog describes his approach to working with someone so volatile and dangerous as being akin to corralling a wild beast. Herzog did not want to ‘tame’ the beast, but rather to put a frame around him, to place enough control upon him to get the desired performance and no more. Implicit in this is a recognition that part of Kinski’s appeal was his volatility, and that the intensity and impact of his performances would be in some way dampened should he be ‘tamed.’ Moral implications aside, this approach is indicative both of Herzog’s fascination with extreme experience and his desire to make work that referred to itself as much as its subject matter.

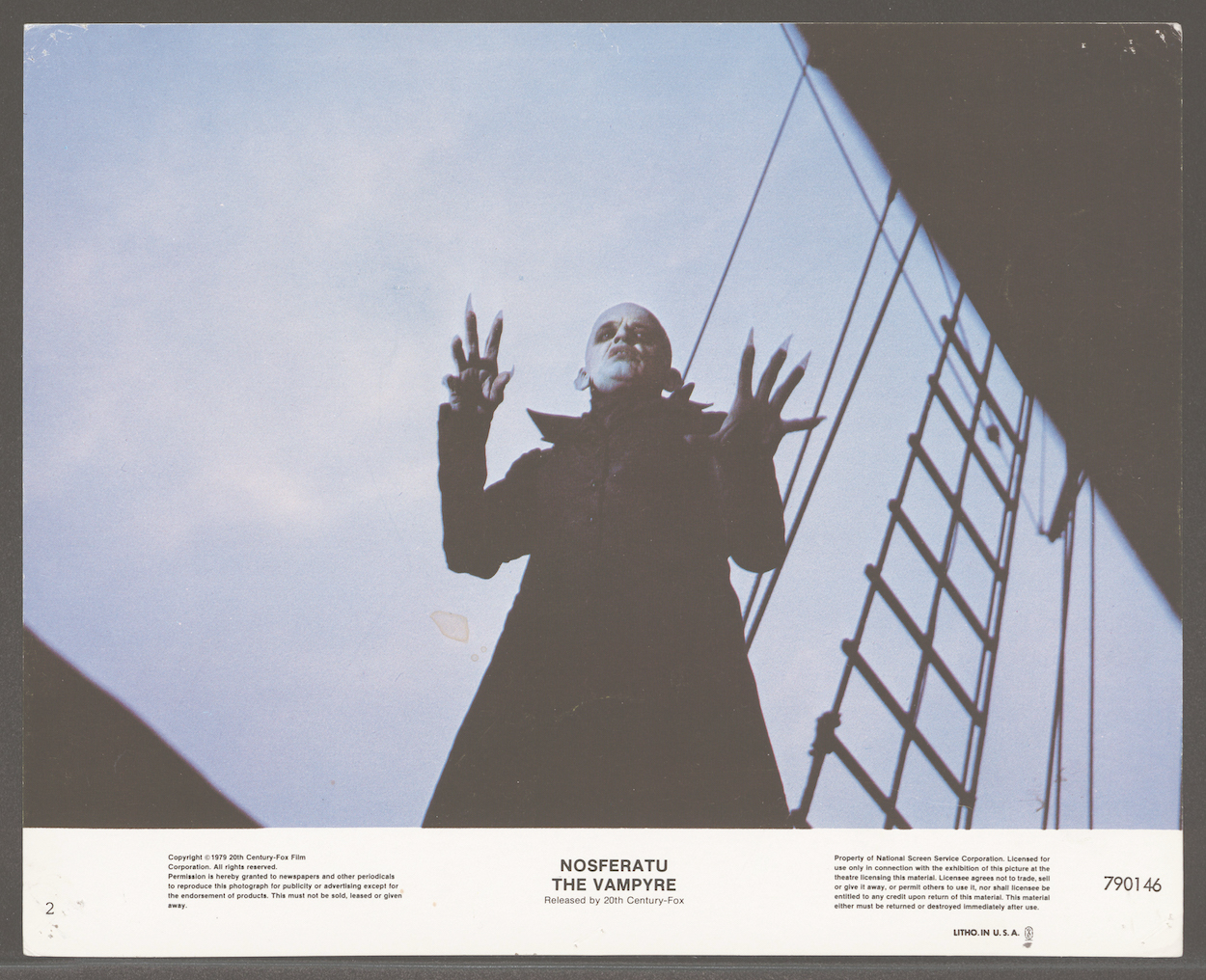

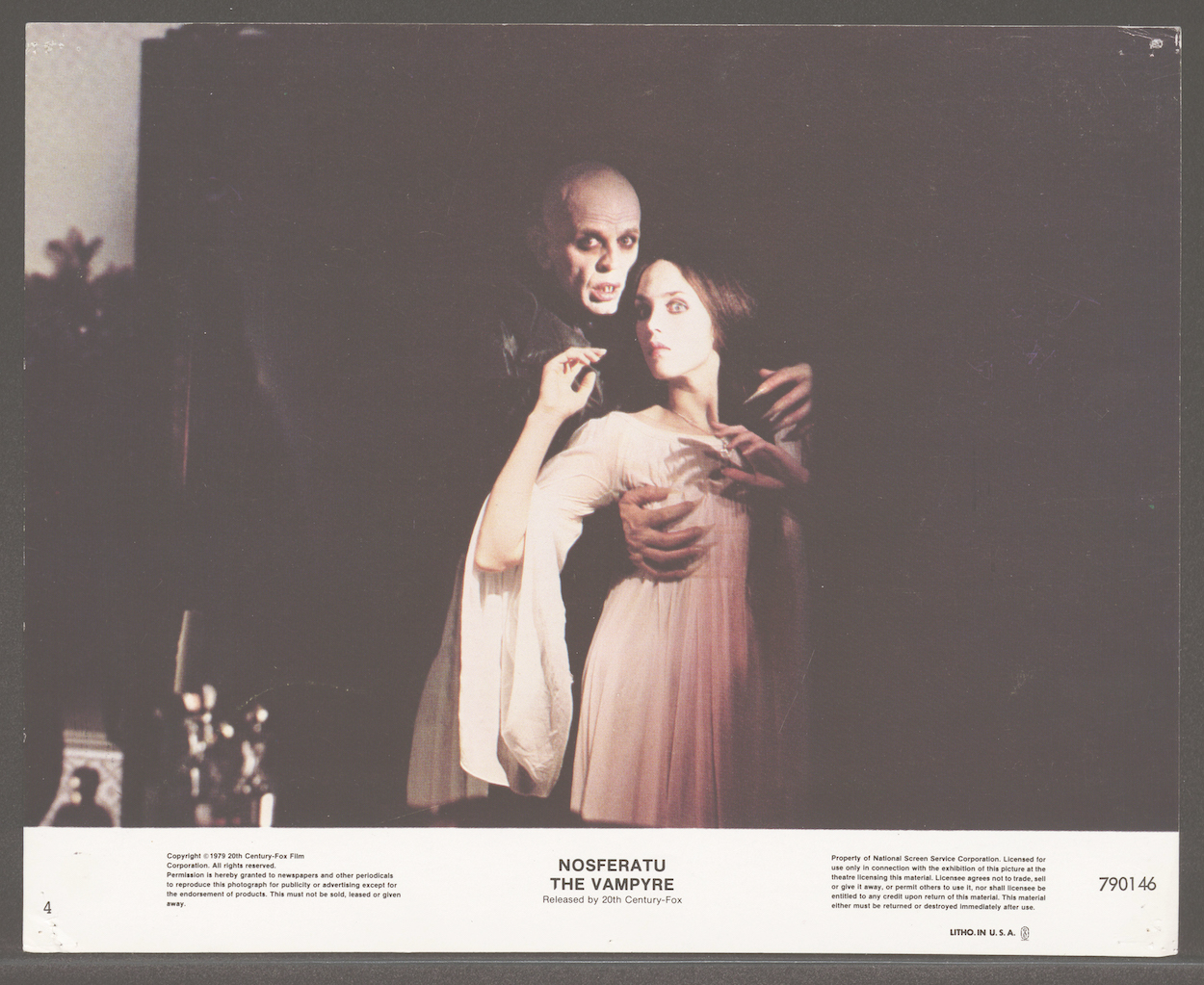

Is Herzog’s Sublime that of German Romanticism? Perhaps not entirely, but its influence upon him is clear. His films, from Nosferatu the Vampyre to Fitzcarraldo, are peppered with beautifully styled images of the natural world, images that render often ordinary landscapes ecstatic and other, and that seem to reveal the essential nature, often hidden, of these places. They are all, to use his phrase, landscapes of the soul, but landscapes themselves do not have souls. Herzogian landscapes are almost always inhabited by people. His films frequently present an ongoing communion between human beings and nature. Throughout his filmography, his characters – in both fiction and documentary films – exhibit awe at the natural world, and often a degree of hubris in believing that they can exert some kind of control or dominion over it. If Herzog, as he has often professed, believes in a chaotic and indifferent universe, and if this view is really at the heart of his films, then why has he always focused on individuals who believe that they can somehow transcend this truth and find something more? Though these people often fail, failure itself is not the point. These people are so fascinating to him, and ultimately to us, because, despite himself, Herzog also wants to believe. Below the cold, indifferent surface of the universe, Herzog’s films point toward something beyond articulation, something ineffable. His films all have an element of mysticism, and he himself is a kind of mystic. Each of his films gestures towards this understanding, a belief that at the extremes of human experience, there can be a wellspring of something that we can never truly comprehend, but that is nonetheless there. In the documentary, he speaks of truth as something that can never be fully seen or articulated, but which exists somewhere, and that can be uncovered obliquely by artists. His films all contain a triangulation, an approximation of that search. Though he purports to have a cold and rational view of the world, he is, in fact, a deeply intuitive and emotional thinker, and someone who even embraces a certain spirituality.

In the winter of 1974, Herzog’s mentor and friend, the German-French film critic Lotte Eisner, became very unwell. In order to visit her, Herzog walked from his home in Munich to the hospital in which she was staying in Paris, a journey that took him more than three weeks. Herzog believed that if he undertook the journey on foot, Eisner would survive for the duration, and if he reached her, she would recover. He believed that this would be possible “through the sheer force of [his] will.” He did indeed reach her, and she recovered to live for another seven years. Eisner later allegedly spoke to Herzog to let him know that she was “saturated with life” but that she would not die, and asked if he were able to lift “the spell” that he had cast upon her. Herzog agreed, and she died a week later. The latter element of the story comes from an anecdote Herzog himself told, so it should be taken with a grain of salt, but even so: These are not the actions of somebody who believes in a chaotic and indifferent universe.

How, then, should we view the often contradictory, always fascinating films of Werner Herzog? This is a man who often revels in being contrarian, has stated plainly that he is not a filmmaker but a poet, and who bristles at every attempt at categorization. Perhaps he is most neatly described as a humanist. His portrayals of human shortcomings, of human tenacity and of human survival ultimately all share a deep sense of compassion for other people. They are entwined with a sensitive and ongoing curiosity for the world and, more importantly, a curiosity for how people strive to make sense of something as huge and as frightening as the universe itself. Across time and space, his films draw connections between different people from wildly divergent backgrounds, all of whom share the miraculous drive of passion, of obsession: something that emerges from a wellspring deep within themselves, and that clearly flows freely from the man himself. This is a body of work – and a man – that says:

To be human is to struggle, but within that struggle resides all that makes life worth living.

According to a survey by dating platform Parship in 2023, only every second person is…

Interview by Benjamin Schiffer

According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, in 2020, only 21% of Americans…

Words by Damien Cummings

The studio is located on the lower level of Quartier 205 on Friedrichstraße 69,…

Words by Marcus Boxler