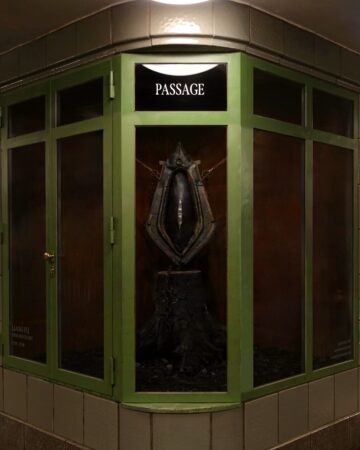

“SPINE BOUNDARY”: IN CONVERSATION WITH LIANG FU (FEAT. PASSAGE)

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…

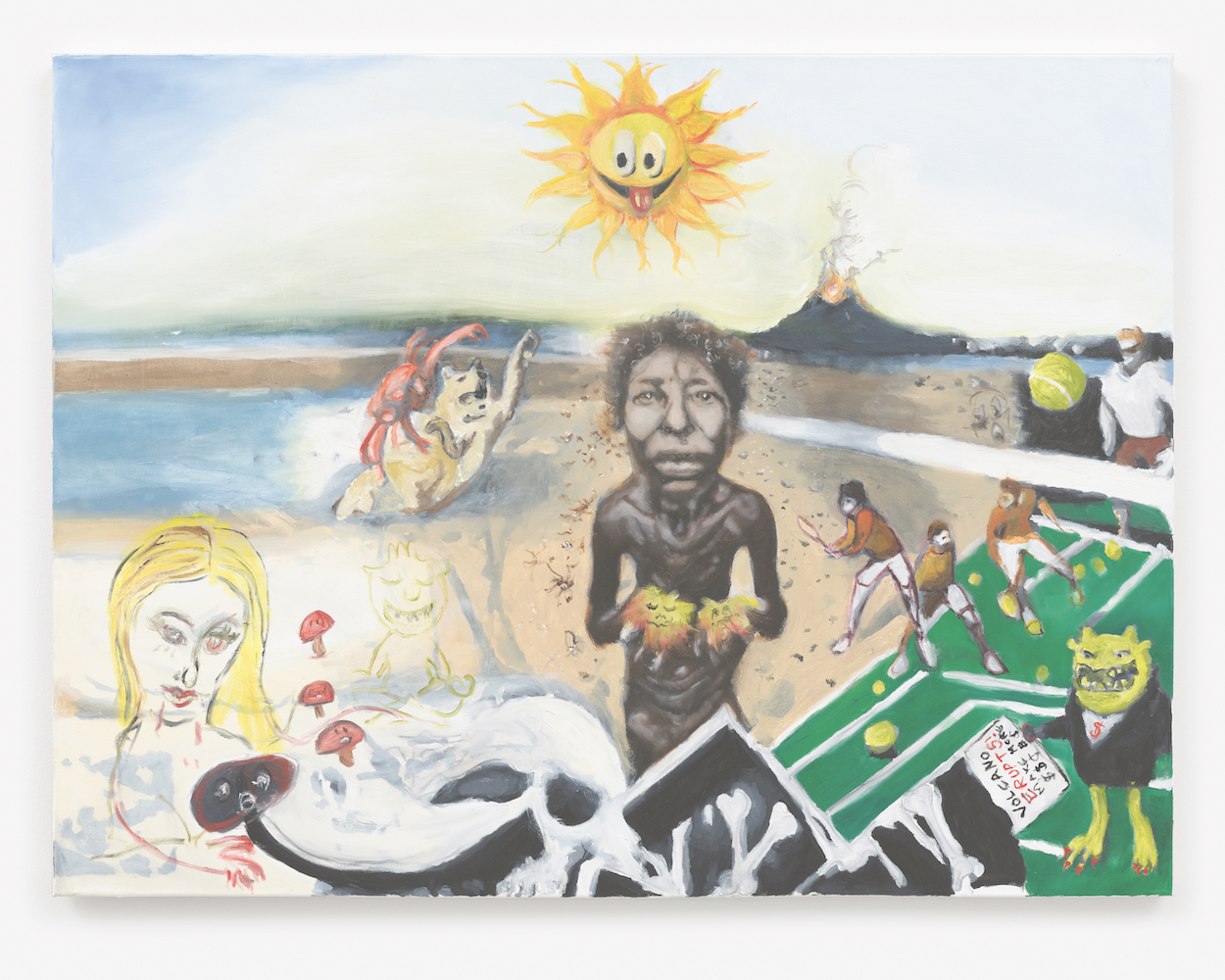

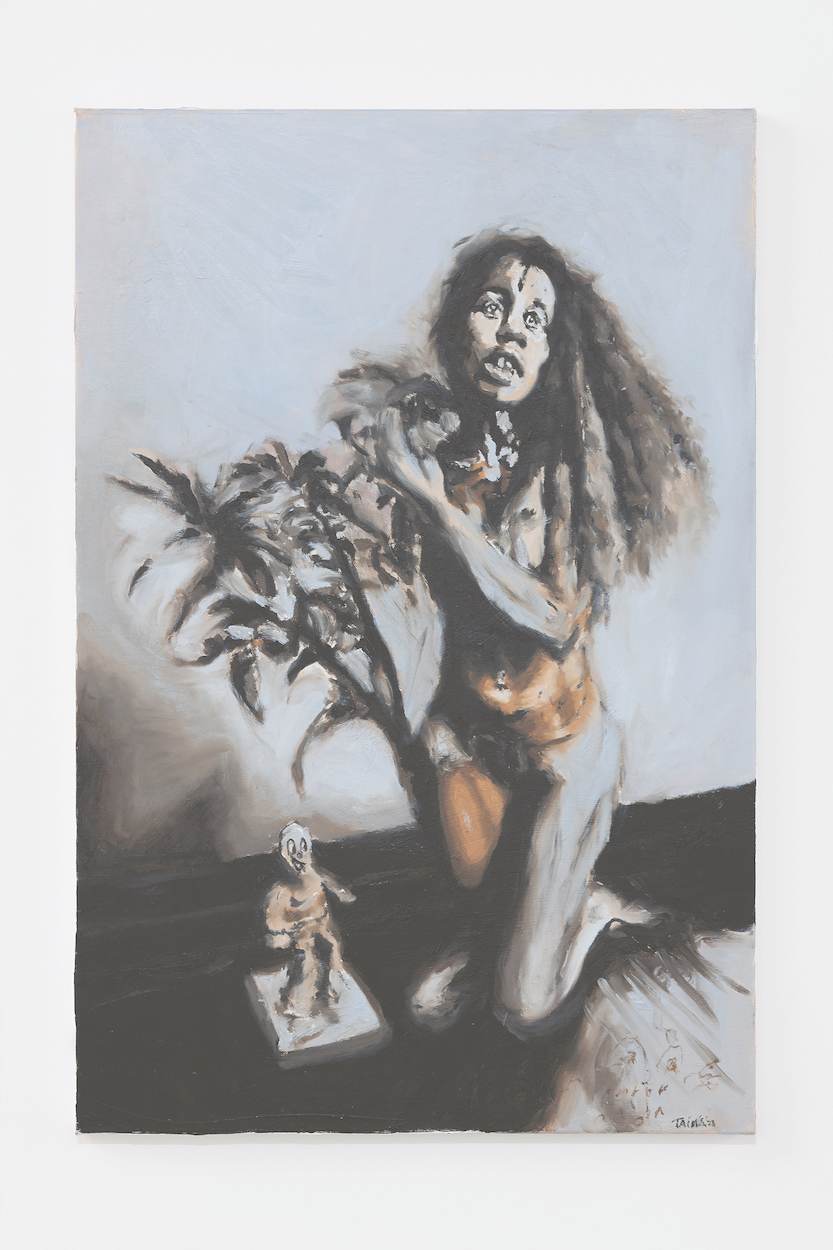

The work of the American interdisciplinary artist and archivist Taína Cruz speaks loudly, to each other, to her, and to its audience.

By creating profound dialogues, she not only continues a family storytelling, but also addresses topics such as mysticism, generational trauma and colonialism. Between paintings, sculptures and 3D animation, she searches for new meanings in indigenous wisdom, using a lot of satire-horror elements. Having studied sculpture in Baltimore, she began painting after relocating to Chicago. Last fall, during Gallery Weekend, she had her first solo show in Berlin. Now, the 28-year-old is back in school to explore and improve her practices.

Taína is in her studio when she answers my videocall with this positive, almost childlike energy – something that her dog also possesses. At times, he jumps into the frame, as if he wants to contribute. A (passionate) conversation about historical lines, horror movies, and the power in playing tricks.

Taína Cruz: It’s going well. I’m taking great advantage of the studio visits; we have about four in a week with the faculty and it is really important for me to get their feedback, especially considering that with a solo studio practice, you don’t really get that much of critical feedback. Also, being in a cohort of really talented artists is great, too, you just feel how everyone is so dedicated to their practice.

Harlem is a very storytelling area; you get a chance to form a community around those who really have generational wisdom and knowledge. And that’s something that has really stuck with me throughout the years. I think those who have seen my work at an early stage were just people in my community and neighborhood; building those long lasting relationships was super helpful for me. It was a tight community, but at the same time, you don’t know everyone. That leaves a nice mystery of what it is that you know and what you don’t know. Also, Harlem is a place that is ever changing, nothing is ever static.

I learned how to just talk to everyone no matter what, so that I can be that well-rounded person who can exist in multiple spaces.

I have to say that the internet was really substantial, the online communities were really flourishing back then, a sense of social presence and community building was starting to form. I realized that at a very early age and have kept that with me always. The internet has totally changed my psyche, for better or for worse, in terms of what is to be expected and not – this is what my work talks about. You think you may understand the painting, but really, there’s just so much more to say about it.

The internet has always been like a second tool for me. I definitely use it less while I’m at school; maybe it’s just because I don’t have the same luxury or leisure time to surf the web anymore, so I am using my sketchbook now a lot lately. I still use Photoshop heavily, a tool they taught us in elementary school. It definitely has allowed me to use it more intuitively. If I need to change a background, a color shift or a body, this idea of manipulation is easier for me to do with digital tools.

Lately, I’m trying to think about the ways in which the painting can be sculptural and I have a really fun time exploring that space. The past months in school, I have been thinking about an installation work that utilizes all five senses to its fullest capacity, so I can potentially just activate paintings to a more ephemeral quality. In general, I look at my work in the long term, like 50 years down the road, 100 years – what do I want to be shown? I ask myself that question constantly; I believe that there needs to be an accumulation of objects with painting and video and sound.

Absolutely. Right now, it still feels like a small piece compared to the big vision.

This definitely is a huge overall theme – horror movie elements allow people to find an easy entry point to my work and it is a useful tool to describe something quickly, at least for now. It’s a way of having a conversation that many people will understand: People know what a witch, an elf or a vampire looks like, it is about world building, whether that’s internally or externally. I am definitely thankful for these horror movie creatures and characters within my overall interest; they also never scare me, my work really isn’t scary at all. I rather find it amusing to be like, “Oh, this is just everyday life, this is just a common, mundane experience.” I like the idea of bringing chills to the body. Horror movies definitely evoke a sensorial experience in the human body and I want my work to bring forth those immediate emotional responses and reactivity. Comedy is a great tool, too. I think it all provides healing.

The unknown is inherently scary to us, and there’s so much that we don’t know in the world; I am just burning with this wanting to know more about it.

Passion really is about finding those mundane moments of walking your dog or making breakfast, trying to find some silent moments; I think this increases longevity.

I am actively working my way through this constantly, it is like an everyday meditative process of how to just find passion even in the extreme, dark, slow, mundane times.

Yes, but there certainly is a thing of having too much passion, whether that’s by external or internal forces. We just have to know how to actively think about ourselves and our bodies and what works best for us. This takes a long time and probably we’ll never really understand what that means. I think at least knowing myself, I do realize the areas in which I am very inclined to feel passionate about creating something versus when I don’t. And it’s really how do I navigate those feelings, how to properly hear myself out so I can make the best work possible, no matter what, even if that’s going to take me until my deathbed. I strive towards that goal endlessly and I think that’s a very romantic way of living.

I do have many rituals to train and cherish the self. I do a lot of active breathing exercises to even invoke that feeling of passion – I use the breath to really reach these altered states of emotions and consciousness. I love to think about the body as a tool to enhance and build life.

I’m taking a lot of classes right now that deal with psychedelics as well. I think we just all love to basically hear about ourselves to really figure out our true human nature and psychedelics can be a great entry point. For me, it is a lot about lived experiences and growing up in a big city. You meet so many different characters who just migrated from various parts around the world and you learn how to interact with so many characters. I’m finding those characters to be very fulfilling in my storytelling – the Upper East Side ladies or the Upper West Side families, the Wall Street people, they all have very distinct personalities. They nourish my art, but when I go into the studio, I enter a moment of pure silence. I just need my very own thoughts to create something. I think people are often afraid of silence since they will be hearing many of their own thoughts and, as we all know, at times, thoughts can play tricks on us. I think I like to play a trick on the viewers with my work.

I like creating works that have a dialogue with each other. Sometimes, I don’t even understand that dialogue; other times, it reveals things I would write into my journal that I don’t necessarily want to be revealed. Knowing how to work with the digital space and that sense of worldbuilding, of 3D animating a fantasy world, I also more and more love to connect this part with the physical painting world.

I feel like any time I make a sculpture, it is a dream project since it requires a few specific working circumstances that make you be less flexible. I also love kinetics and machinery, to create sculptures that move and activate them, give them humanistic movements – a machine, for example, that can breathe. My big dream is to work with an engineer instead of DIY’ing my own motor with a battery. I would love to work with a professional engineer on a large scale moving object from a video or a painting that I’ve made.