How did that start? Have you always done that?

I think on the premise of a self-sufficient and self-enclosed territory, that is not made as a riff on another territory or inopposition to another territory.

So, like, its own territory.

It is its own territory. It is also a device to check on the intensity and accuracy of the object.

When you work on paintings, do you start with preparatory drawings?

I don’t draw, but I take notes on little scraps of paper to not forget the image I want to make. But when I make the painting,there is no preparatory drawing at all. Everything I make is done that way, to unprepare myself to make it.

So, it’s the opposite of preparation.

The opposite, I just make room and then let it unfold.

And the title of the cycle is The Waves? Or do they have individual titles?

The individual title comes later. It’s been two weeks and they don’t have a title yet. I’m looking at them and then if I see that there is a theme…

Here, the wave is almost gone, there is almost no wave.

There is no wave. The wave is the most distinctive element in this group, but not all the paintings have waves in them.

And what prompted the waves?

I have no idea. I do as I’m told.

So it’s like Whistler said – art happens, it just happens, art just happens.

Whistler. So, like, higher forces tell you. [“Art happens – no hovel is safe from it, no prince may depend upon it, the vastest intelligence cannot bring it about.” – James Whistler, Ed.]

I think it’s a little late to find excuses, no? [laughter]

And this?

This is super recent; it was painted yesterday. So, it is a different register and technique than these…

How was this painted? What is the different technique?

The technique is different and also the entire article is different.

It’s like a palimpsest, no? So many years in the studio.

It has been there for a very long time and a friend of mine took a photograph of it, showed it to a club owner, who made a neon sign modeled after it and put it in the club.

It is interesting in the series that this painting is so different from all the others.

It’s a little more of a complicated image. I actually saw those two once in Los Angeles at the Sunday fair, the Sunday market. There were a boy and a girl and they were walking around. Without the snail, just with the leash.

It’s so connected. It’s like an interspecies dialog between the snail and them, it’s beautiful.

Also, this is more layered. I’m very very much enamored with this technique.

When did you start with it?

And these are new watercolors?

These are new watercolors, yeah.

Is that the same rock garden?

Another rock from the same rock garden. [laughs]

And the watercolor practice is always parallel. Is it something you always do?

Yeah, it also depends on the location. When I’m In India, when I’m in New Mexico, when I’m in the Caribbean…

This is all super recent.

Also this year?

Very recent, yeah. June. [unwraps more]

This is an amazing series, does this have a title?

It’s one set; I like to keep it together. It can be “Rock Garden”, or it can be “Four Seasons.” Then there is another set. When you have enough, you tell me.

No, I’m very curious. I just don’t want it to be difficult for you, I’m curious to see as much as possible.

Ok. This is one set I made in June 2023, and the other set is a group of self-portraits.

And you made these in New Mexico?

All of this was made in New Mexico.

So, how does the work differ from studio to studio. Say, in New Mexico, is it more watercolors?

Well, paradoxically, this really enchanted, spiritual, soulful, fragile place takes me to a very layered, grotesque, dark place. So, I confine myself to watercolors because the dark is too much. If you translate it into watercolor, it will not have theheaviness that you would have if it was painted with another medium.

What about the self-portrait? Because the self-portrait appears from the beginning, in the 70s already. How did that begin?

As you know, when I began to paint, painting was supposedly entirely forbidden and discredited. And I lost everyone’s friendship, including Alighiero [Boetti].

Really?

But why? Alighiero made lots of painting on paper?

Yeah, but he didn’t think he did, you know?

So, he was against your painting?

So, it was ideological?

Yeah, totally. He didn’t think he was painting, because he thought he was applying the process. And also he was delegating. A lot of those works were made by Tirelli. He wasn’t even painting with the hand. You should not see the hand, the subjectivity.

Which is paradoxical, because he painted rather hand.

It’s complete nonsense. In any case, because all of that, I felt I took ground. I didn’t take painting for granted. I said ok, I’m going to be a painter. A painter of what? Who is painting? And then I thought, well, I am painting. And what is the subject of the “I painting”?

It wasn’t about sensuality, it was not about self-something. It was really about the fragility of the self, the discontinuity of the self. This is me chasing away the bad thoughts, the negative thoughts. But then, as they were leaving, I felt very sad for them. I thought, where are they going to go?

Amazing.

Think about it: Even bad thoughts have the right to have a life, no? [laughs, unwraps more artworks]

This is also amazing, what were the thoughts here?

I’m just a burning match. But I am very pleased with this setting: Because I painted them where I painted them and at that particular moment, the technique is completely different than my usual watercolors, which were much more deliberate and very carefully done.

It’s more open.

It’s messier. And I really really like this.

Yeah, it’s beautiful.

This is another set, five self-portraits.

They’re completely different from your previous work, more free and loose. I mean, they’re always very liquid, but here it’s more…

They’re totally open. You know the signature on my watercolor is the address, that is always precise. And here, they’re open.

I remember when we first met, you said you never use photography in the poses. So, you work from memory?

I mean, I look at things, yeah, but I don’t… There is no information in photography, visual information. It’s veryimperfect. It’s a reduction of what we see. I mean, we don’t see as little as that. We see so much more than that.

Yeah, it’s so much more multisensory, than photography.

Also, all the lines are always false lines in photography.

Maria Lassnig, the Austrian painter, always said painting and drawing can go where photography cannot go. Because photography cannot go into our nerves.

That is true on every level. Also on the optical level. I mean, I am not an optical artist. But, for me, photography doesn’tgo where the soul is. Not only that, it also doesn’t go where the eye goes, you know? It’s just not good enough.

Do you paint every day?

Yes. Well, I mainly paint, but also just sit here like this.

Oh, wow, this is amazing. What are these?

This is how I spent my pandemic.

I got really obsessed with these. At the end of the 19th century, a Japanese archeologist, who was a tutor at the Emperor in Mongolia’s court, asked permission to leave and went to a remote corner of northeast China. He was there to dig these, and claimed that they were from 2000 BC, from this unknown civilization. And the iconography, very strange and original, is the pig. The fetus of the pig is the most important image. These people also made vases.

I suspect that this man made it all up. In any case, nothing happened until the 30s, there was a little bit of digging. And then in the 60s, there was more digging. They found ten thousand objects and nine thousand got stolen. And then, inthe 80s, they started to surface on the market, and many many forgeries were made. But the forgeries were made bypeople who never saw the originals because the originals are too rare. So, the question is: Maybe these forgeries are originals, made by people trying to imagine this remote civilization, and I think whichever way it is, it’s fantastic. [laughs] Then I went to the British Museum; they have a couple of “originals.” Well, the note of the curator was: “Probably a forgery from the 20th century.”

But, they kept it in the collection. So, if the British Museum keeps it, I can keep them also. And Christie’s or Sotheby’sHong Kong are like, “Oh, what we have is from an old Chinese family…” so the price is shooting through the roof.

But you found them for a few dollars on the internet?

Yeah, during the pandemic.

And here?

My mother. She was a painter.

Did she exhibit?

But she felt as an artist?

My mother’s claim to fame is that she, during the war, traded the tires of her car for a beautiful 18th century Neapolitanboiseri secretaire. Those were her values, you know. [laughs]

And this is another series here?

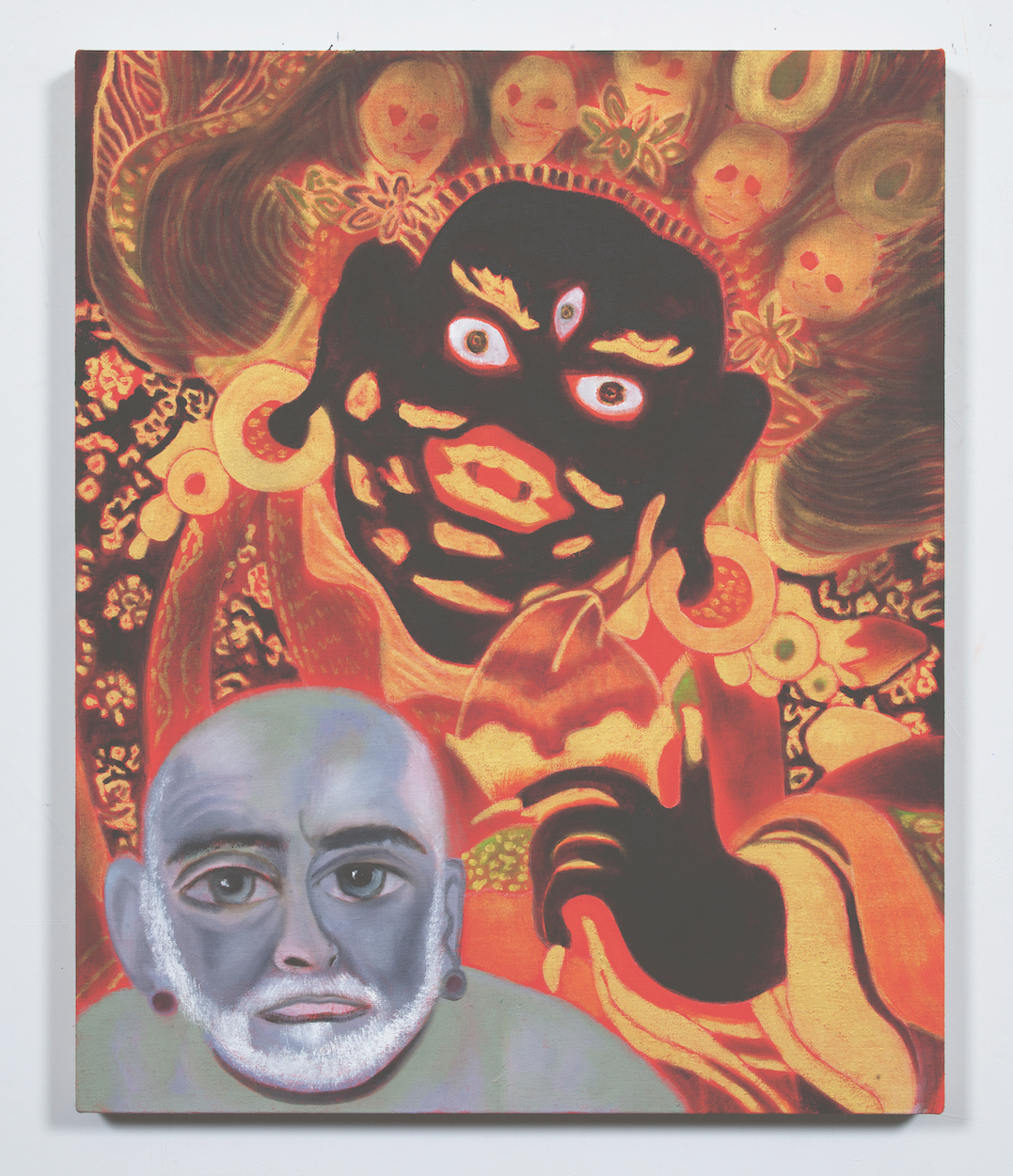

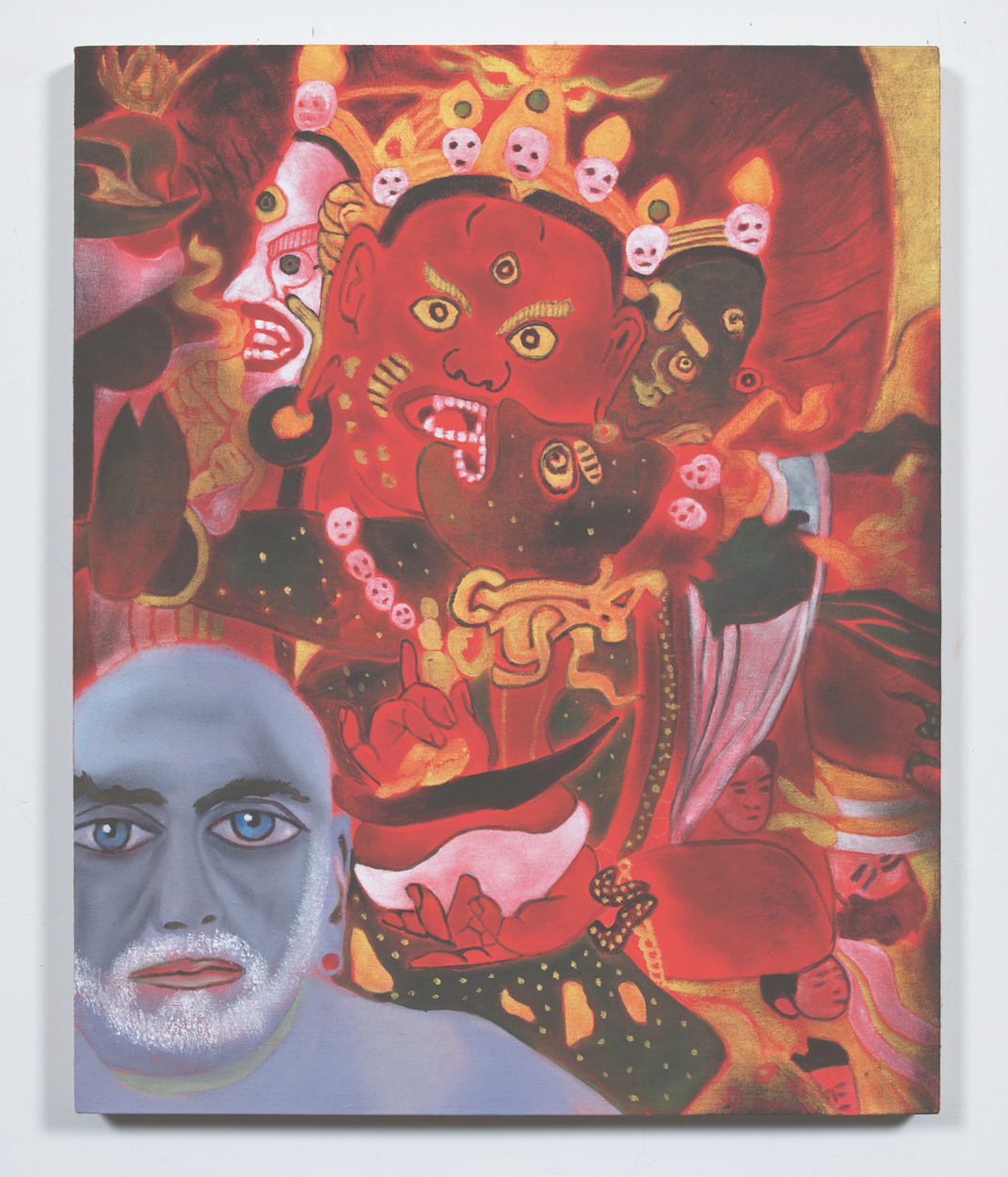

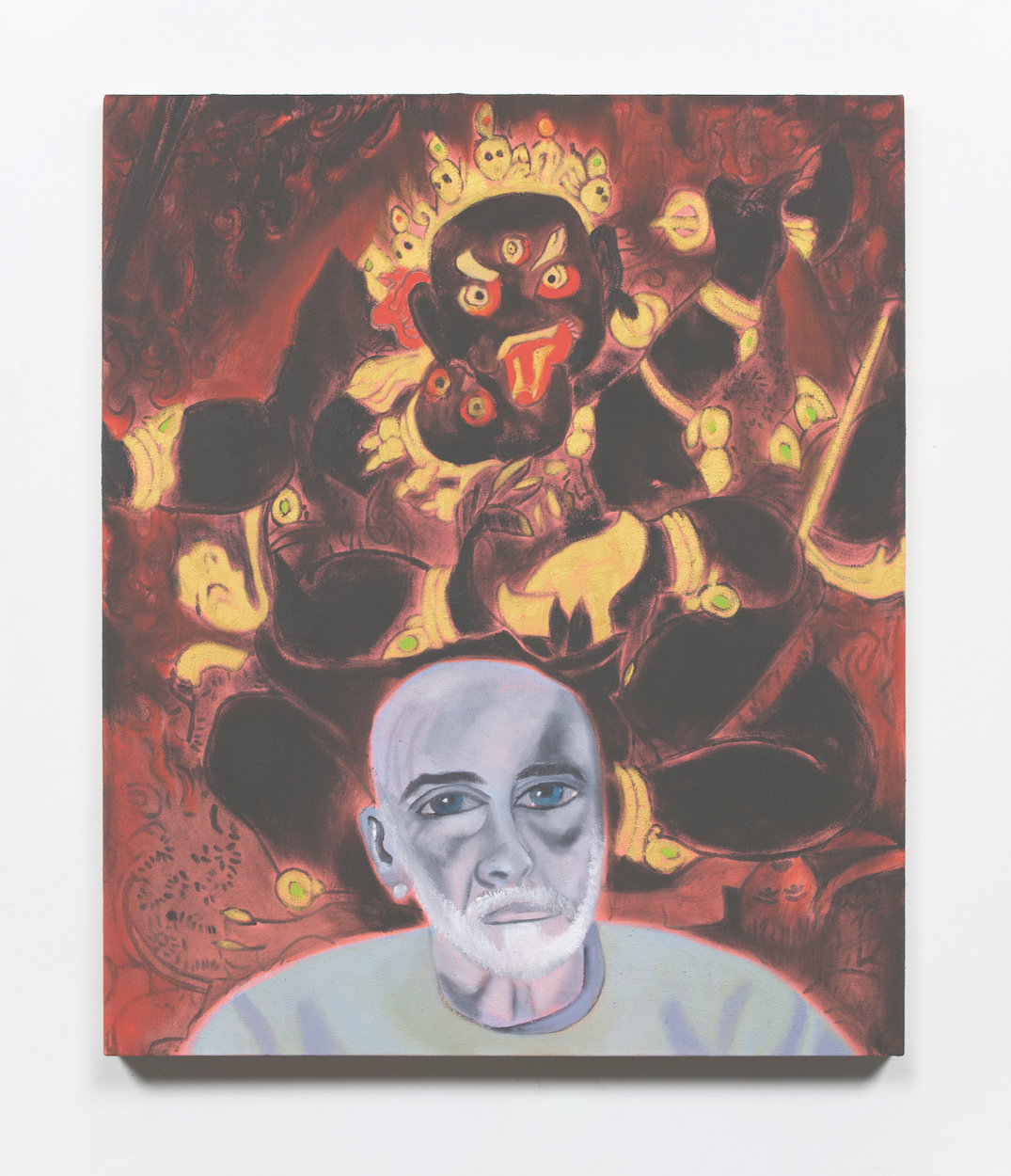

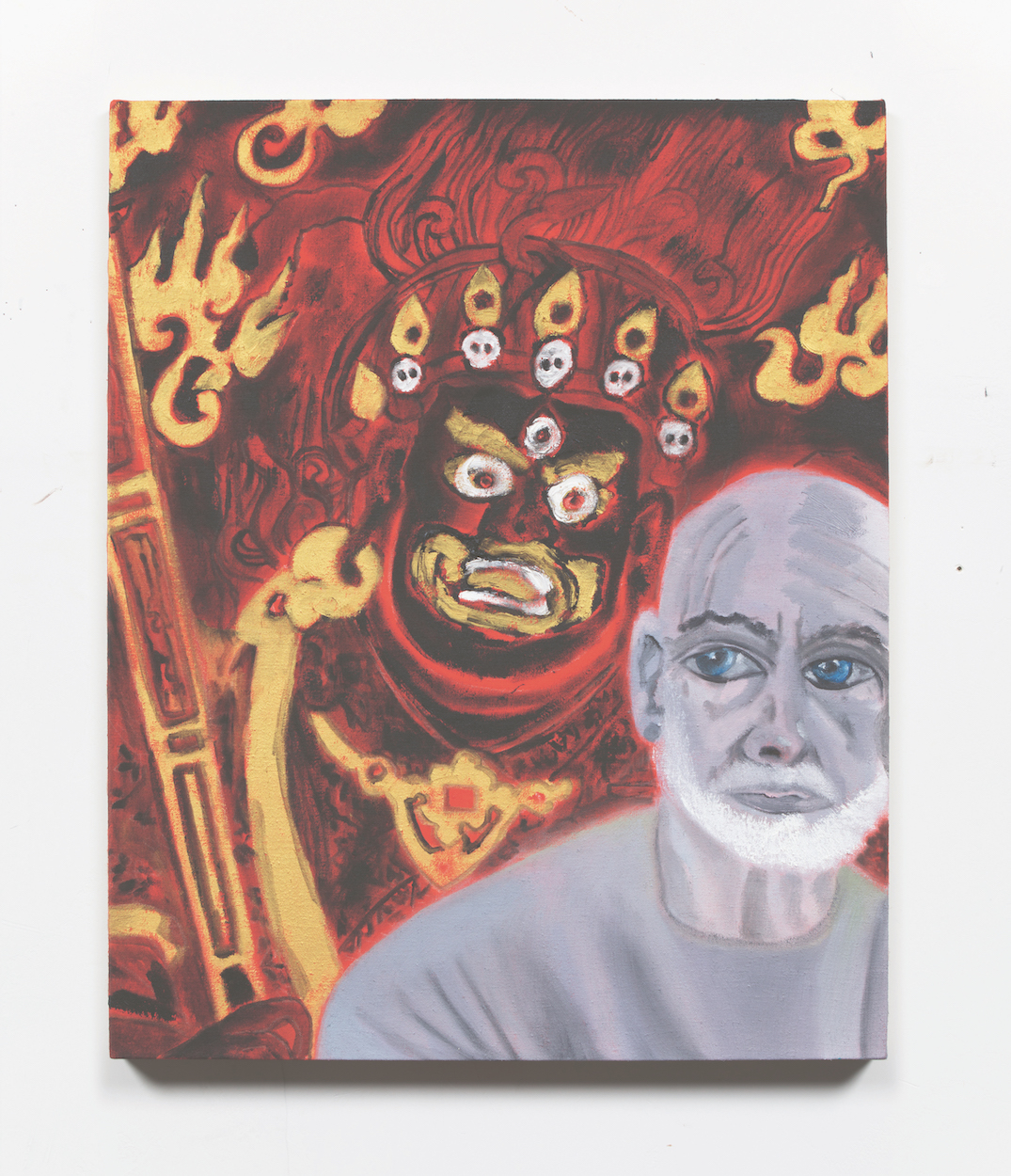

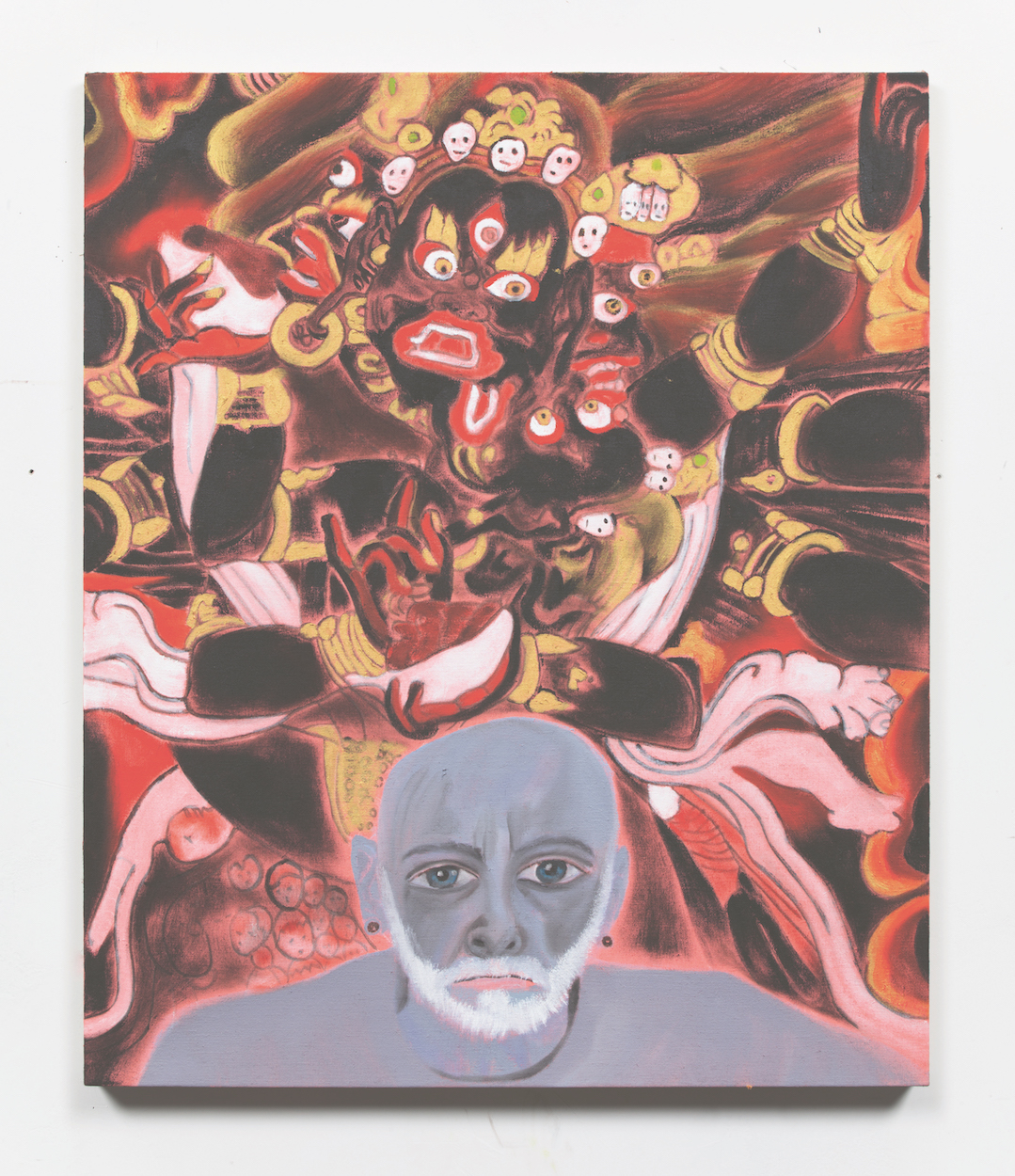

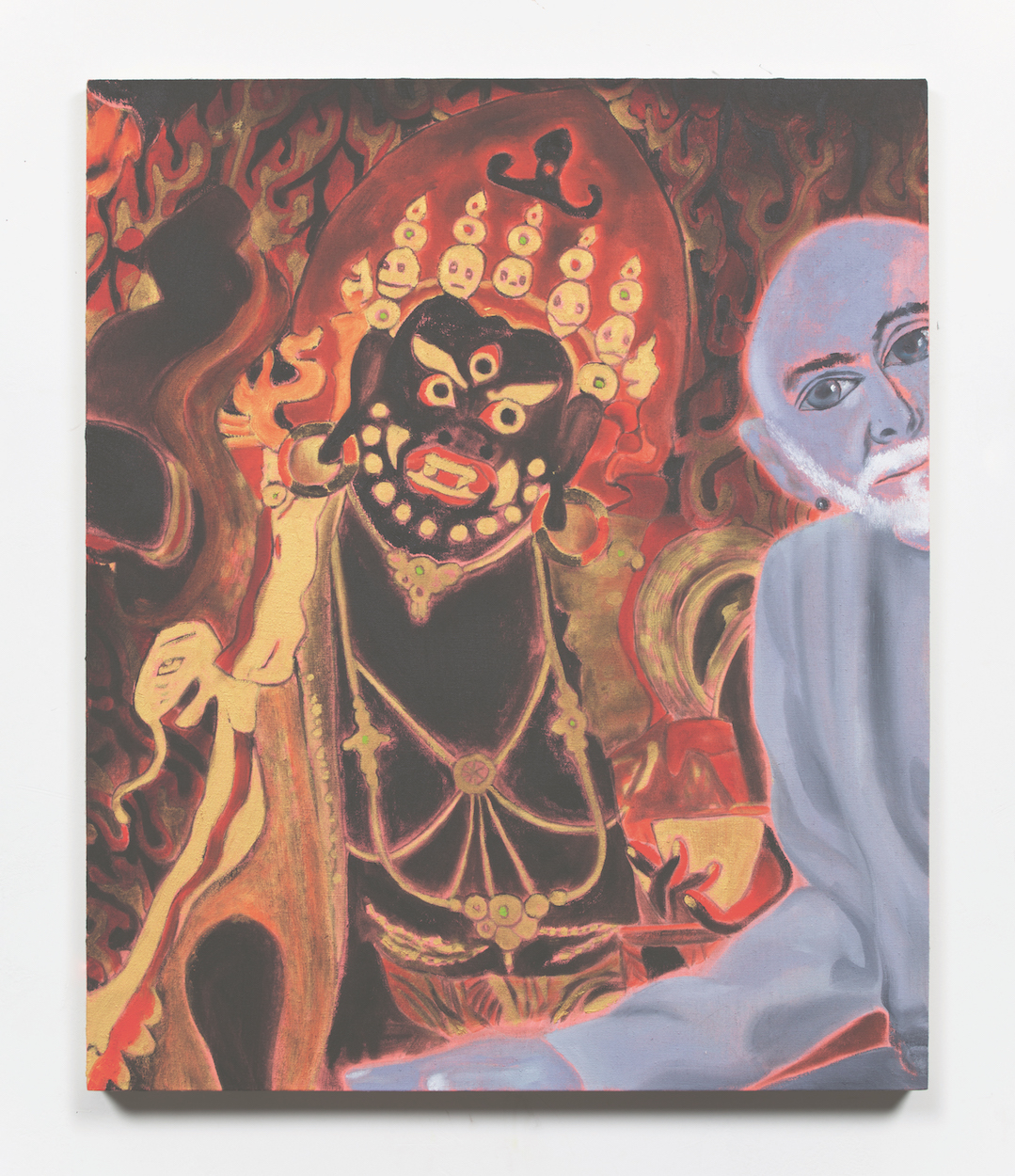

These are self-portraits in the Bible. So they’re self-portraits with all of the deities that we see in the bardo – bardo meaning the state of existence between lives.

And the wall painting?

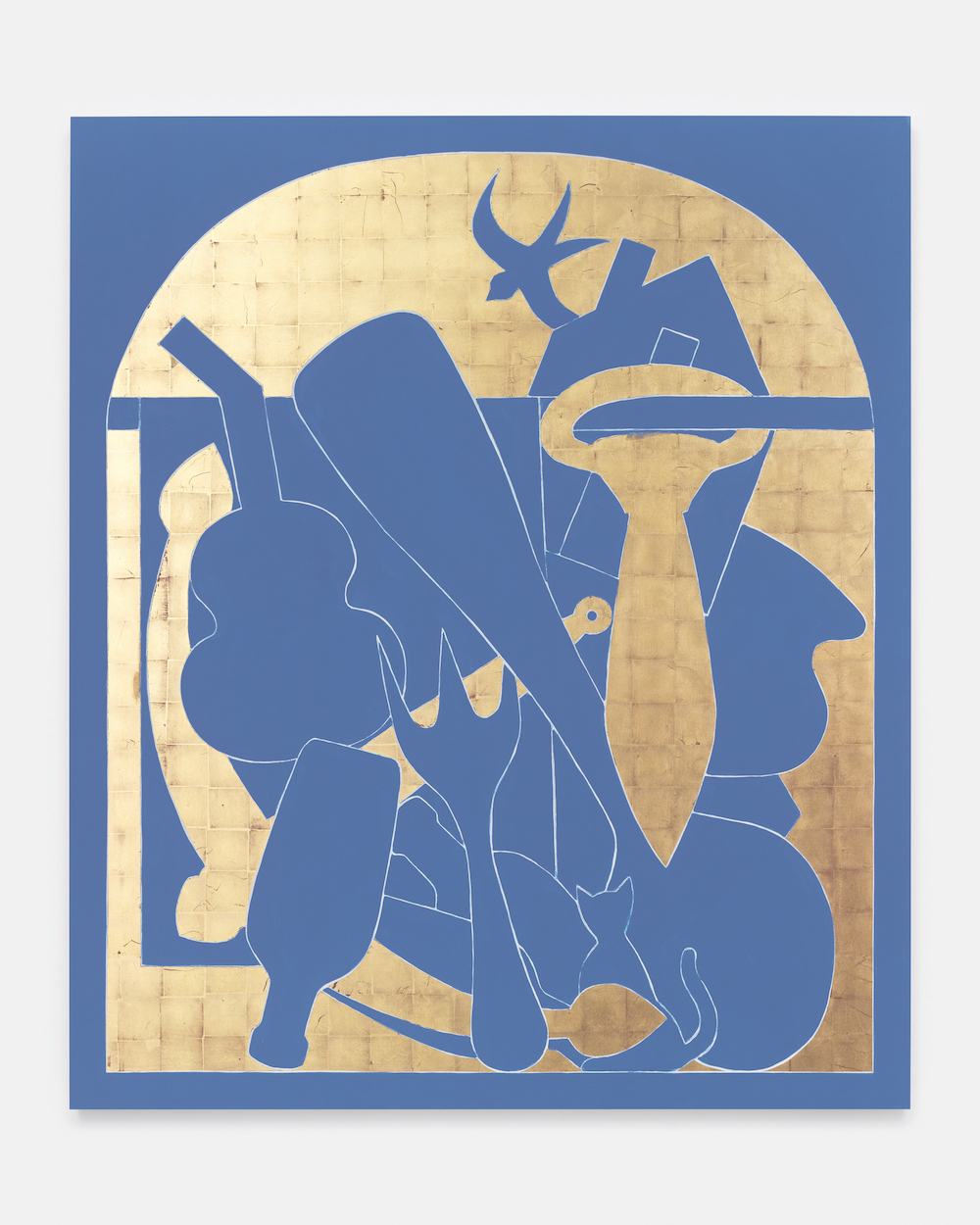

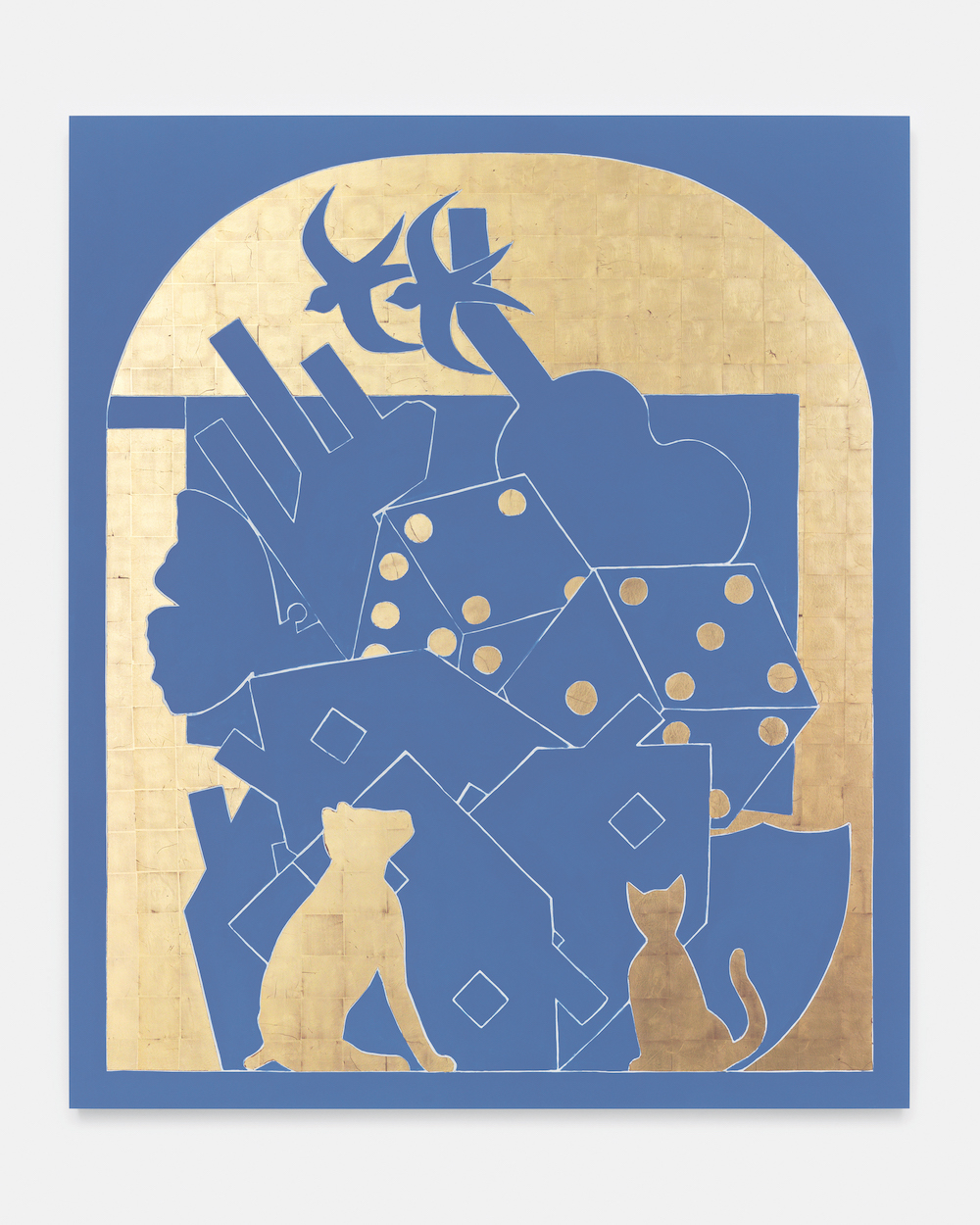

The wall painting is something I’ve been doing in the past few years, since China. I made the first one in China, I had a big exhibition in 798 in Beijing. And then I did another version in Dallas at the Contemporary Museum, and then I did another in Berlin. They’re big murals, where I draw the shapes. And then, with a couple of assistants, we do it in these standardized ways, with oxblood.

It’s interesting because the other day, I spoke to some younger artists who all have the desire to go back to wall painting and frescos. Because, in a way, this whole art world, where everybody travels, it’s not sustainable, it’s not ecologically sustainable. So there is a desire, but you’ve been doing it for a long time.

I’ve been making frescos for a long time, but my frescos are movable, like that one. And recently I’ve beenmaking them again, but I don’t make them here. I have another studio in Greenpoint where I make them.

So, you have a whole studio for frescos?

Yeah, because it’s a real thing, you know, with water and plaster.

How did your interest in fresco begin?

My first one, I painted it for the Venice Biennale in 1980. I was friendly with a restorer in Italy. I came to New York in1980, I saw the frescos from panels at the Met. And when I went back to Rome, I thought, why can’t we actually make them on the panels? And so we did. It’s a big triptych. Three meters by six. It was shown at the Biennale curated by Harald Szeemann.

So, the frescos, are they all movable, or did you also do site specific works that are not movable?

I did a few non movable ones. The main one is in the Museo Madre.

That’s the one I know. I saw your big show there, which was fantastic. And this is recent also?

This is recent but not super recent; I’d say maybe two years?

And this is another one in this series?

No, this is by a friend of mine, a young painter.

Who is it?

Her name is Priya Kishore. She’s Indian.

And this? Because it’s quite similar to this.

Maybe. I don’t think she’s derivative of my work. She spent a lot of time here. She has that quality that you have inIndia. She watched me working and she really absorbed all my tricks, but she has very much her own mind andsensibility. That’s a drawing by Alba. This is an artist in Mexico City. These are all women. That’s a work by my assistant.

I want to create more, but then the moment passes and it’s difficult to go back.

[they move around]

This is the first canvas by Basquiat. The first time he painted on canvas.

Oh, wow. Very very first time?

Yeah. Diego Cortez did a show upstairs from the Mudd Club. It was a group show. And this was in the show.

It’s an amazing piece.

It’s very powerful, you can really see how much energy and sense of space.

And these are your books here?

These are the necessary books, which means Sylvia and poetry.

Poetry has always been very essential for you.

Poetry is very important. And then these are my formative books, when I was a child. The first French edition of the 1001 Nights, illustrated, which was my sexual education, the illustrations are so dark. [laughs] And this is a discredited bookbecause I think this guy was a fascist. It was illustrated with these ink drawings. When I was growing up, like, let’s say at six years old, these two books were my parameters.

And in poetry, who are your poets? Because you did a lot of collaborations with poets.

I collaborated with Robert Creeley, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Rene Ricard, Vincent Katz.

And recently?

Recently, I’ve been working on a book from a writer from the 1920s that I discovered.

And this is another series of paintings?

These are the Tibetan monks, but they’re unfinished.

It’s really such a magical place here, so many layers.

It’s good. It’s a good place. I love this wall with my friends’ work and my assistants’ work. With Julian Schnabel on topthere. I love the palette of it all. And then the map I made a few years ago. The best part of the map would have been if someone would have been there, recording my rant about all these lines. Because the oldest lines, and now again. I mean,look at this bullshit here. You know how many people died for these lines? Like, millions. And now again, millions. Right here, look. Look at the lines. So stupid.

Like the war in Ukraine.

Yeah, look. You can tell that there are problems there. Look at the lines. Look how many lines. It’s two thousand years. It’sa bit misleading here because there are no dates. Because if you would have dates, you would see now France, Spain, Germany, England.

Is this was a series or a one off? Because I have never seen anything like this from you.

And it’s also a continuation of Boetti very differently, no?

It relates to all of those things, yes.

I think Agata [Boetti] is a special person.

I think she really gets it.

She’s really devoted and committed and she’s smart.

The book she wrote about Alighiero, it’s excellent. She really caught something. She got the voice. And for a child, for thedaughter to hear the father, it’s a miracle.

Yeah, it is. And what about this here, this altar?

These are altars from Hindu worship and altars from Tibetan worship. Within the Hindu, there are many different deities and counts. This here is Vishnu, this is Ganesha, the middle one is Tara. The big crystal is actually from a tantric temple in Benares [Varanasi]. And then Shiva, Shiva. I love those chalk objects. They belong to the Lingayat. And glass paintings from Tanjore. Giant drawings.

And these drawings?

Jain. I always loved them. There was a high end art gallery in Turin in the 70s, Sperone Gallery, and they had thisexhibition of gigantic Jain cosmologies. That was just a transformative moment for me. There were a lot of magic squares;I made several works with the magic square.

So, your earlier drawings or paintings in the 70s were inspired by that?

You don’t have a catalog raisonné, but if it would exist: What would be the first work in it? What’s the first work you were happy with, which was no longer student work?

It’s a drawing that ended up on the cover of a big catalogue. It’s a self-portrait of me with a raised fist, like a communist salute.

So it begins with a self portrait.

Yeah. There are drawings that I made, in a thick book like this, when I was 19, on my first trip to India. That’s a page fromthat notebook.

So it all began in India then.

The early works were actually photographic works. I don’t know if you noticed.

I know.

Because I would not show the original drawings. I would take a photograph and then show the photograph.

So it was more conceptual.

Yeah, so that nobody would give me a hard time, you know, so Boetti was happy, everybody was happy. [laughs]

It’s interesting that it was so ideological.

I think I was very lucky. I mean, it was so much better than going to an art school or anything like that, you know, to be with these remarkable people. And they were all really incredible people. Pier Paolo Calzolari was a wonderful person, wonderful artist. Mario and Marisa Merz – they were difficult, but they were amazing, too. To be confronted with someone like that. Luciano Fabro.

[Giovanni] Anselmo?

I was not in touch with him. They were the outcasted, the Turin group – Anselmo, [Giuseppe] Penone and [Gilberto] Zorio were considered lesser people.

Really?

It was very competitive you know? [Jannis] Kounellis.

[Luigi] Ontani?

Ontani was my friend. Because Ontani and Boetti and I, we came to Rome at the same time. So we were also outcasts at the beginning, because there was an established group of artists in Rome. And they looked at us like, who are you? What do you want? We were included in an exhibition by Sargentini, it was called “24 hours.” The gallery was open day and night. That’s how we all met, and that’s where we were confronted by the local artists who were up in arms against us.

What did you show there?

I showed a cluster of tiny drawings, but projected through the lines into an empty room. And there were anamorphic drawings. So, with the projection being on an angle, they would go back to being regular.

You use the book as a medium a lot. You did a lot of artist books and of course the Hanuman press. Was that also from the beginning, or how did that book obsession start?

So you made artist books already in the 70s?

Yes. Have you ever seen Art & Project? The little red one?

No, it would be great to see. And there hasn’t been a book about a book?

No. [He gets another book] You never saw this?

No, I’ve never seen it. In Latin. Switzerland. The Swiss flag.

Christianity, the three religions and the three drinks. Coffee for the Muslim, wine for the Christian, and tea of the Buddhist.

And was this produced in India?

So it’s pre-Hanuman press?

Yes, but that’s how I met the press, which then published and printed the other books.

These are all drawings and watercolors?

No, some are drawings, some are paintings on tin, like the shop signs in Madras, which are painted on metal. These entire works have been kept together in Groningen, in a museum.

Is this a painting?

It’s a photograph of a painting. It only exists in this format.

Is this your very first book?

No, it’s the first book made in India. But I had already made two books in Italy. One with the architectural modifications,and another one with these drawings.

What prompted the architectural modifications?

Well, you know, I did go to architecture school. I didn’t take the last exam, [but] I did the entire thing.

[Reads out loud] “Printed by: Kalakashetra Publication and Press, Madras” So that’s where you did Hanuman, no?

There’s a whole Hanuman revival at the moment.

This is amazing. And the other one?

This is the catalogue of the Peter Brant exhibition and it includes the enormous watercolors that I made. See, these are gigantic, like 60 feet. I painted them in one scroll and then I cut them. And this is a collaboration with Allan Ginsberg.

What did you do with Salman Rushdie?

We made a book. He wrote a story for me. It’s called “In the South.” It’s really fun. It’s a story of two old men arguing about life. One hates life, and the other one loves life. They argue about the two points of view. We printed it when I hadthat exhibition in Naples. It was beautifully painted there, in my hometown.

What came first, the images or the text?

The text. I really understood what a great writer Salman was because every sentence was a picture. I mean, literally, every fucking sentence was an image.

So he produced images and you produced images, in your different ways.

We are very close. I’m going to see him tomorrow night. We have an anniversary gathering.

Is he okay now?

Yes. The anniversary of the stabbing – I think it’s genius. [laughs]

So, you did the letters but the sentences are from him?

Yes. With Ginsberg, the calligraphy was Ginsberg’s calligraphy. But in this case, it’s my calligraphy.

I had this great interview with Salman Rushdie and we were talking about archives. He was telling me about his archive of all his emails and all his letters and correspondence with the university. The whole challenge of that, because it’s very difficult today. In the past, it was easy because we had letters and now it’s all in email and WhatsApp and text. And when you send someone a letter now, it’s a different thing because with an email, you would never think of it being published. It’s complicated. He was saying that there need to be arrangements, that maybe for 50 years, they are not publicly accessible, but maybe later on. I learned a lot from him about archives. He is very interesting on archives. I mean, he’s interesting on everything.

Whenever I do correspond with him in writing, he really makes all the points as concise and non-literary as possible, just super factual.

Are there many more such books like this?

This is one that has never been reproduced. And there is the one with John Wieners. This is an art book with just religious posters and my drawings, back to back.

With Creeley, I made more than one book. That’s a very nice one, because it’s done with a beautiful printing process. Grenfell Press. Beautiful. Some of these are rare now. This is something I did with Gregory Corso, where he wrote a long long beautiful poem after these gold paintings. We made a vitrine with all the books.

So, in a way, this is the book about the books, but not yet completed.

Yeah, it would be so nice to do that.

Allen Ginsberg lived one happy year in a giant loft because of his archive. He sold it for what seemed an enormous price to some institution, I can’t remember which. And with the money, he finally got out of this tiny apartment onAvenue A and moved to a big loft. But then he died only a year later.

But he had one year.

He had one year in a nice loft. He died at the same age and from the same disease as his father.

The last thing I want to ask you about is architecture, because I’m really interested in this whole relation between art and architecture. I began my entire research to visit artists because of Vasari, because lots of artists loved architects. Now, our society is quite divided. But, at the same time, a lot of artists do architecture and a lot of architects do art. So it’s really interesting that you bridge, in a way, art and architecture. I saw your show at Mary Boone before she closed the gallery and it was very beautiful. So I want to ask you about architecture, because I didn’t find anything in your interviews or books about this relationship.

Well, nobody ever asked me, but also, maybe I don’t know the answer yet. [laughs] So, definitely, a relation must be there,but frankly, I don’t have the answer at this moment.

But, you did study architecture for four and a half years.

I did study, and I was in an architectural studio, working.

With whom did you work?

Just other students, we had a studio together. But they were older than me.

Were there architects who inspired you at that time?

Frank Lloyd Wright. That’s why I build furniture. When I came to New York, to me, he was like a mythological figure. And, all of a sudden, I realized I could actually live with his furniture. I couldn’t believe it. You know, they were giving it away when I came to New York. It was completely out of fashion.

It’s really beautiful, the furniture. So, Frank Lloyd Wright – what inspired you about him? The connection to nature?

Yeah. And the East. And this fantasy of America, which, you know, we have before we come to America.

And then you did this book with the architectural modifications. Can you talk about that?

The title was “Pierre Menard,” which is Borges’s story. Borges, at that moment, was also a big influence to me. The idea of everything being connected, in a way, with fictional identities, impersonating something or someone. Now, I don’t evenremember how the Pierre Menard short story works, but it inspired the idea that you can make these imperceptible changes and what the value of that is. The older photographers manipulated, too. These were the official portraits of ten iconic architectural buildings in the years of modernism, yet all the photographs were manipulated so that the proportion was slightly off, or changed. Everything I’ve made has to do a little bit with Chinese whispers. It’s based on the idea of miscommunicating.

But corrected architectures are never meant to be built, are they?

No, the idea was simply to test how flexible this is. Modernism is kind of inflexible. So it was a test to see, is it really so? Does it really have to be that way? I don’t trust in flexible.

Utopia is flexible.

Utopia is flexible, yeah.

The poet Eta Landmann wanted to be an architect in the beginning. Like you, she started in architecture, but she said as a woman in the 50s in Lebanon, she couldn’t become an architect, it was not allowed. But she always had this dream of designing her own house. So she made a plan, and it’s now being built posthumously, this house in Lebanon. So, I was wondering, based on your architecture background, if you ever had any architectural projects, like buildings you wanted to do? Your own studio, your own building, or anything else?

Yeah. I would like to have a nondenominational chapel, for sure. That’s totally up my alley. There are things in one’s lifethat are just dormant, and they have to be dormant, they have to be asleep until it’s time to wake up, you know?

That’s beautiful. So, almost like the Rothko chapel, not related to a religion…

No, not related to a religion. Because I’m not a Puritan and basically, my sensibility is not tied to the religions of the book. Because I prefer community-based sensibilities and perceptions and experience-based religious constructs. Notsomething that comes from the outside. So, if I was ever to make a non-denominational chapter, it would be the sum total of many religions rather than the absence of many religions.

Do you have drawings or sketches for this chapel?

I keep it in a confused and shadowy corner of the room, where I can’t really see the outlines.

But the piece which I saw at Mary Boone, “Standing with Truth,” was, in a way, the idea of a tent and an architecture. How did that happen?

Yes, completely. Yes, it is an architecture.

And how did that happen?

I adopted this particular shape as the perfect story that is up my alley. Because it’s a story of contamination in the sense that you find this shape in mandapams, like temples in southern India from the 17th century. You find a shape like that, but then you look at military tents of the British military in India and you find the same shape. So this is just a layering offorms, which lead to this particular form – which is a standard form – except I chose the measurements, but the structure is a standard structure that is used, let’s say in today’s India for weddings or for celebrations or with things like that.

And why is it called “Standing with Truth”?

This is from a beautiful poem by Kabir. He said something to the effect of I sit with truth, I stand with truth, and maybe Isleep or I lie down with truth. Basically, a reminder of the necessity for the correct gesture and for awareness in movement.

Was this the only time you ever did such an architectural structure, or have there been others?

No, it’s the only time, but I made six tents like this. With six different themes and titles. There is the “Museum Tent,”which contains self-portraits, and then there is the “Taking Refuge Tent,” and then there is the “Pepper Tent,” which was shown in the Kochi Biennale.

HUO: And then, of course, a link to architecture is when you do works in-situ. Like when you do a fresco on a building, or I suppose the permanent works.

Some great artists, they favor a very neutral presentation of their work. I don’t favor that. I pay great attention to where thepainting’s going to hang, how far from the floor it’s going to be, or how far from the other paintings it is going to be. I’m very keen. I tend to always be involved in the hanging of my exhibitions, and you may call that an architectural sensibility. I like for the space I’m in to look good. And to have a spontaneity about it and not to be tight.

And do you have any unrealized public art commissions like the 1%, the public art commission?

No. There is an intimacy about what I do. It really is not my register. I think the tents are a very exceptional event in mywork, because I think they do keep that quality. They’re tactile, they’re intimate, they’re soulful. When you enter into therealm of public commissions, it is extremely difficult to keep that quality in the work. I don’t think I’m capable of doing it.

Richter says: “Art is the highest form of hope.” Do you have a definition of art?