“SPINE BOUNDARY”: IN CONVERSATION WITH LIANG FU (FEAT. PASSAGE)

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…

From Microscopic to Monumental

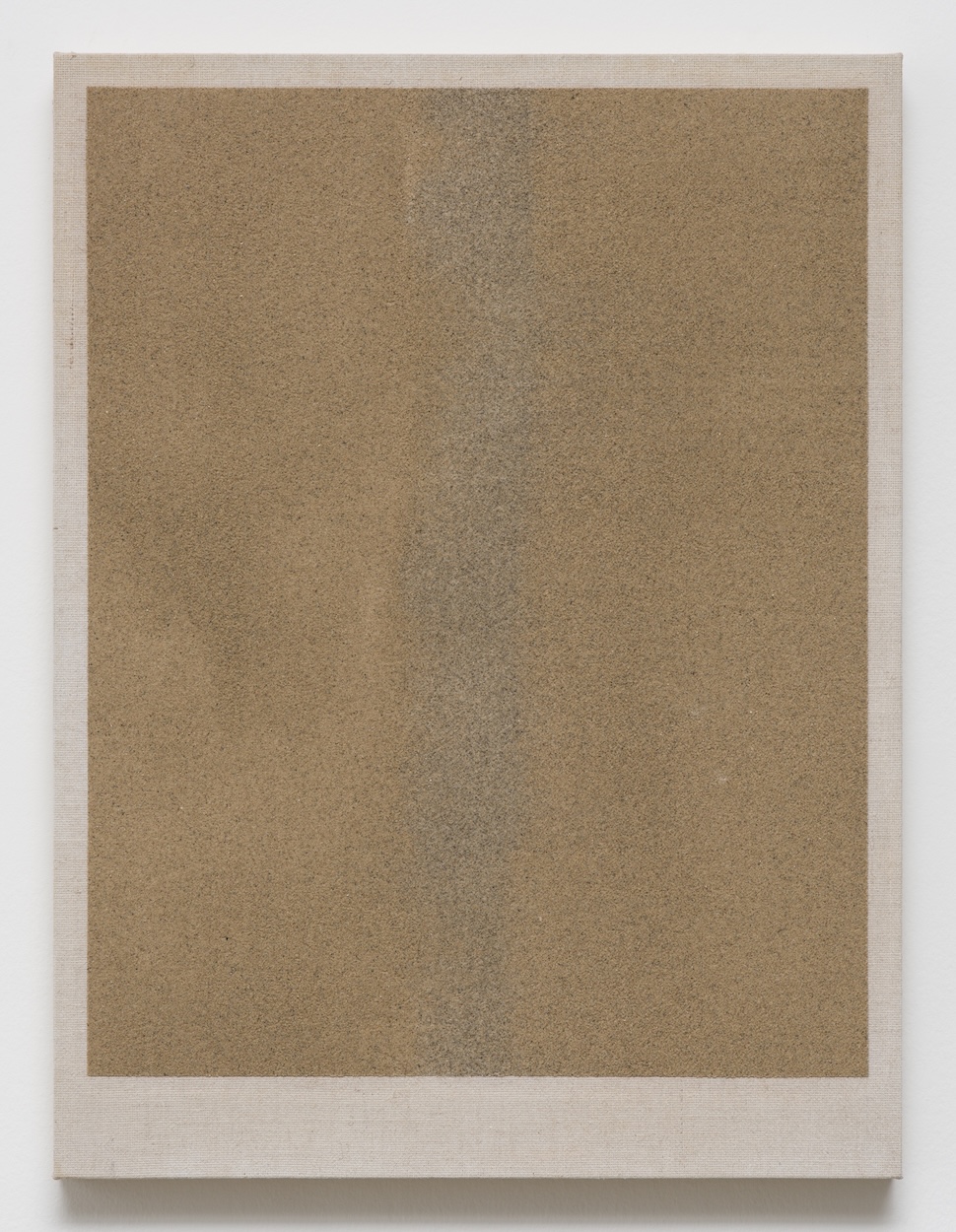

From grains of sand to towering sculptures, Jeewi Lee’s work transcends the boundaries between art, science, and philosophy. In her latest exhibition, Fields of Fragments, Lee, literally, invites us to see the world through a new lens—examining the hidden histories embedded in the seemingly mundane. A journey through memory, materiality, and meaning.

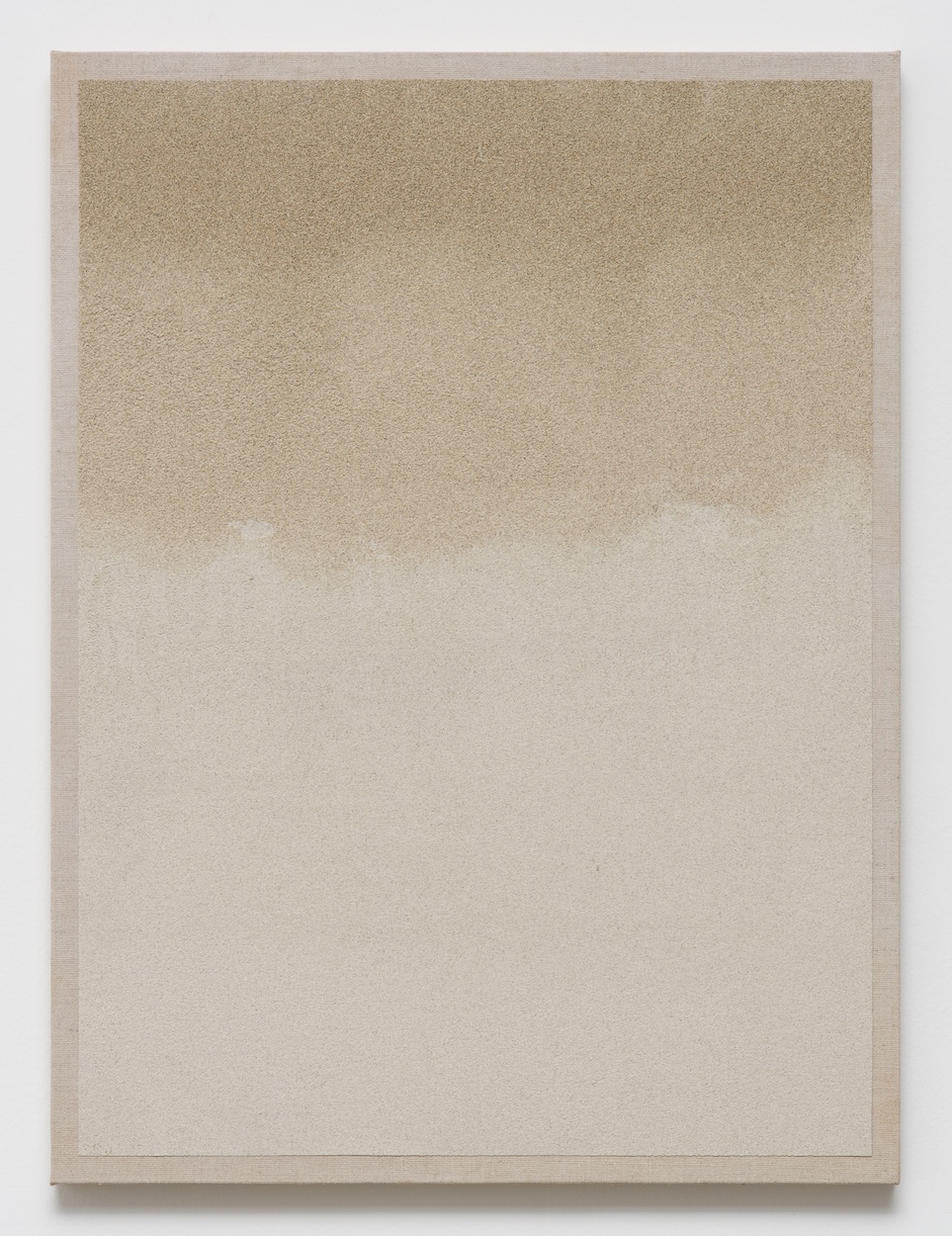

Jeewi Lee (JL): My fascination with sand began about three years ago during a residency in Portugal. Initially, it was the aesthetic qualities that caught my attention—the striking orange and ochre hues of the sand along the coastline, which seemed almost luminous under sunlight. This fascination with its color and form led to a deeper, more conceptual engagement. This material, often overlooked as mundane, carries incredible geological and metaphorical weight. I started researching sand and quickly realized its paradoxical nature: it’s seemingly infinite yet finite, a resource deeply embedded in our everyday lives, but also one that’s rapidly depleting due to overuse and exploitation. At the same time, I found it deeply personal, as I began to reflect on its biographical connections to my own life.

JL: As a child, I moved frequently, often every two or three years, which made it difficult for me to establish a sense of belonging or connection to a single place. This rootlessness shaped me profoundly, and I struggled with feeling ‘out of place.’ In working with sand, I realized it follows a similar trajectory. Sand is created by movement—the more a grain travels, the more polished and rounded it becomes, bearing the marks of its journey. This parallel between my personal experiences and the life of a grain of sand was both a revelation and a source of comfort.

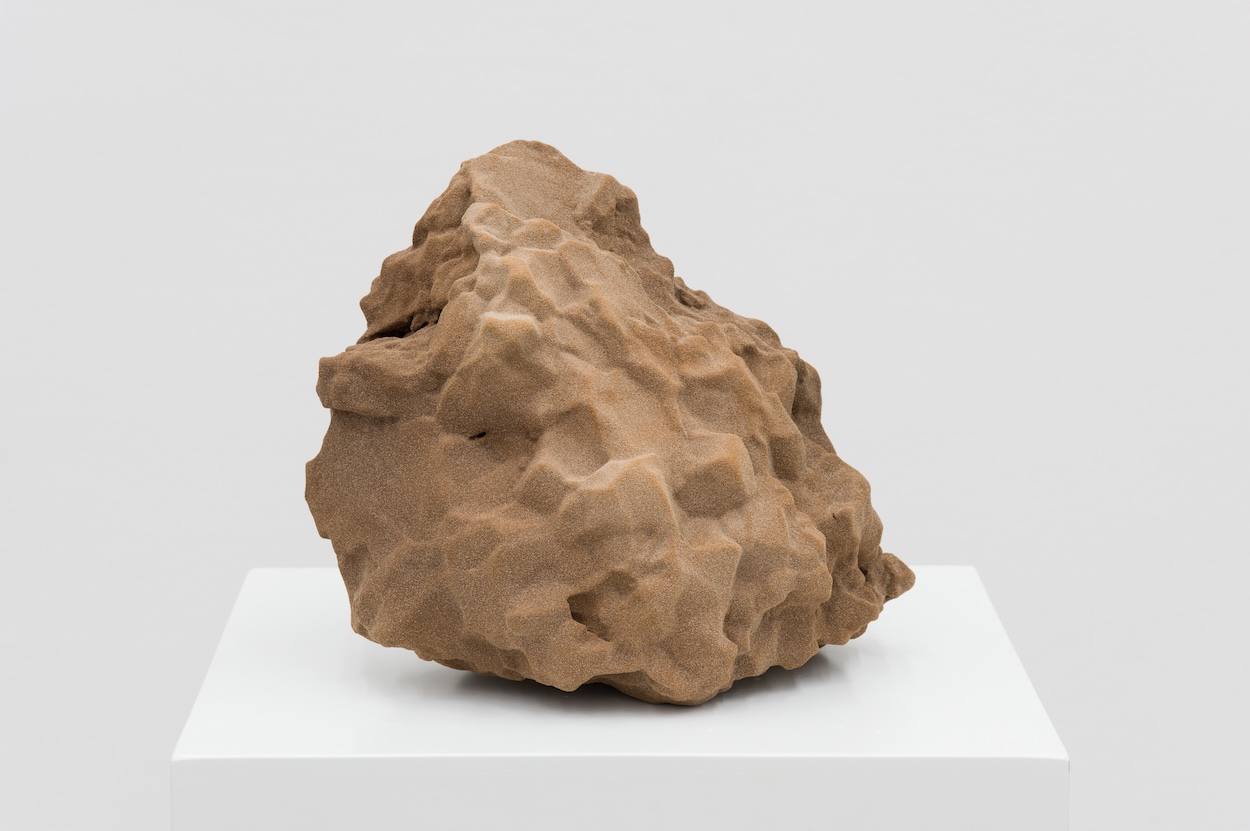

JL: Each sample of sand in the exhibition tells a story tied to its place of origin. I collected sand from sites with personal or artistic significance, such as the West Coast of South Korea, Dakar, New York City, Mallorca, and Alentejo in Portugal. The process was intimate; each grain felt like a fragment of a larger narrative. In Senegal, for example, the sand’s tar-rich tones stood out, while in Mallorca, I discovered tiny fossilized coral and shell fragments. These characteristics became the foundation for both the paintings and sculptures in the exhibition.

Sand is deeply symbolic. Each grain is unique, shaped by millions of years of erosion and migration. Yet, in a mass, its individuality often seems lost.–Jeewi Lee

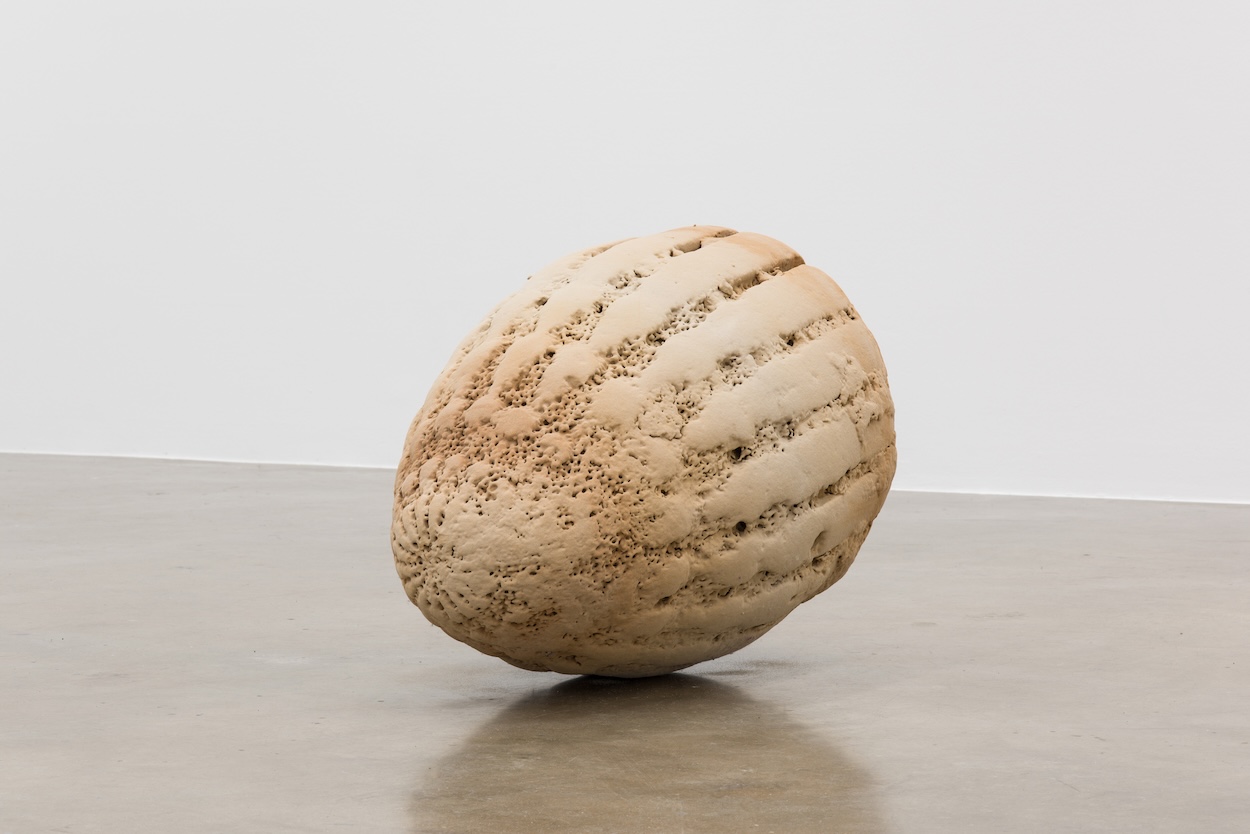

JL: The sand paintings and sculptures complement each other: versatility and individuality. The paintings are often monochromatic, though some have delicate gradients. Just like the subtle variations within the sand from each site. On the other hand, the sculptures, magnified many times from individual sand grains, transform the microscopic into the monumental. I was only able to realize this complex project together with geometry researcher Phillip C. Reiner. The sculptures reveal the textures and forms that are usually invisible to the naked eye. Together, these pieces highlight sand’s dual role as both a ubiquitous material and a vessel for unique histories.

JL: Sand is deeply symbolic. Each grain is unique, shaped by millions of years of erosion and migration. Yet, in a mass, its individuality often seems lost. This mirrors humanity: we often perceive ourselves as insignificant within a crowd, but each person, like each grain, carries their own story. Additionally, I was struck by the fossilized remains embedded in sand—miniature time capsules of past ecologies and landscapes. These “embodied memories”, as I call them, underscore the passage of time and the interplay between permanence and impermanence.

JL: One memorable challenge was translating the sculptures from the microscopic to detailed visibility. The difficulty began with selecting the “right” sand grain—one that could represent the material’s complexity. Transporting these grains to the Zeiss laboratory posed its own issues. Early on, we used simple envelopes for mailing the grains. On one occasion, two grains arrived instead of one. For days, we puzzled over this “spontaneous division” until realizing the grain had broken under the pressure of the postal stamp. Still, it became unusable… Another time, a grain seemed lost entirely. Imagine the panic! Eventually, it was discovered wedged inside the cap of its container.

Once at Zeiss, the process of nano-CT scanning required exceptional precision to capture the intricate structure of each grain. Afterward, magnifying the scans into sculptures via 3D sand printing presented additional hurdles, including managing weight, structural integrity, and surface texture. It’s an extensive, technical process. Each step required meticulous collaboration among artists, engineers, and scientists to bring these grains to life as monumental forms. Especially, in this context, Phillip C. Reininger’s knowledge in Geometry was substantial.

My work often seeks to make the invisible visible.–Jeewi Lee

JL: This duality is central to the exhibition. Each grain carries traces of ancient landscapes, such as coral reefs or volcanic eruptions, but when enlarged, they evoke human-made structures. One sculpture, for example, resembles a column. It’s unmistakable! It’s also a hint at our innate tendency to seek patterns and familiarity.

JL: Yes! This interplay between the natural and the constructed creates a tension. This tension is the coexistence of past and present, and that is exactly what I want to make tangible in my work.

JL: My work often seeks to make the invisible visible. With Fields of Fragments, I aim to draw attention to the overlooked—the sand beneath our feet, a resource we take for granted yet rely on immensely. Similarly, in MUTE, I explored the subtle boundaries between presence and absence, sound and silence. Both projects encourage a tolerance for ambiguity, inviting viewers to sit with complexity rather than seeking definitive answers. We both know each other from my work at the Skulpturenpark Schlossgut Schwante. There, I created a site-specific piece that must literally be sought out. I found a tree with a branch that had been amputated, leaving a void. I replaced the missing branch with a prosthesis—a cast bronze replica that fills the gap and is secured to the tree. The piece engages questions of oxidation and whether, over the years, the bronze will stand out or blend seamlessly with the tree, which at the time of installation made the prosthesis nearly indistinguishable. Ultimately, I hope to evoke a sense of wonder and reflection about our place within larger systems, be they ecological, social, or temporal.

JL: Or: Attempting to see the world from the perspective of a grain of sand. In the end, the complexity of the bigger picture is not so different after all (smiles).