Supercontinent “fashion”: Numéro Berlin in conversation with Emanuele Coccia

Sometimes, says Italian philosopher and author Emanuele Coccia, we forget that for a long…

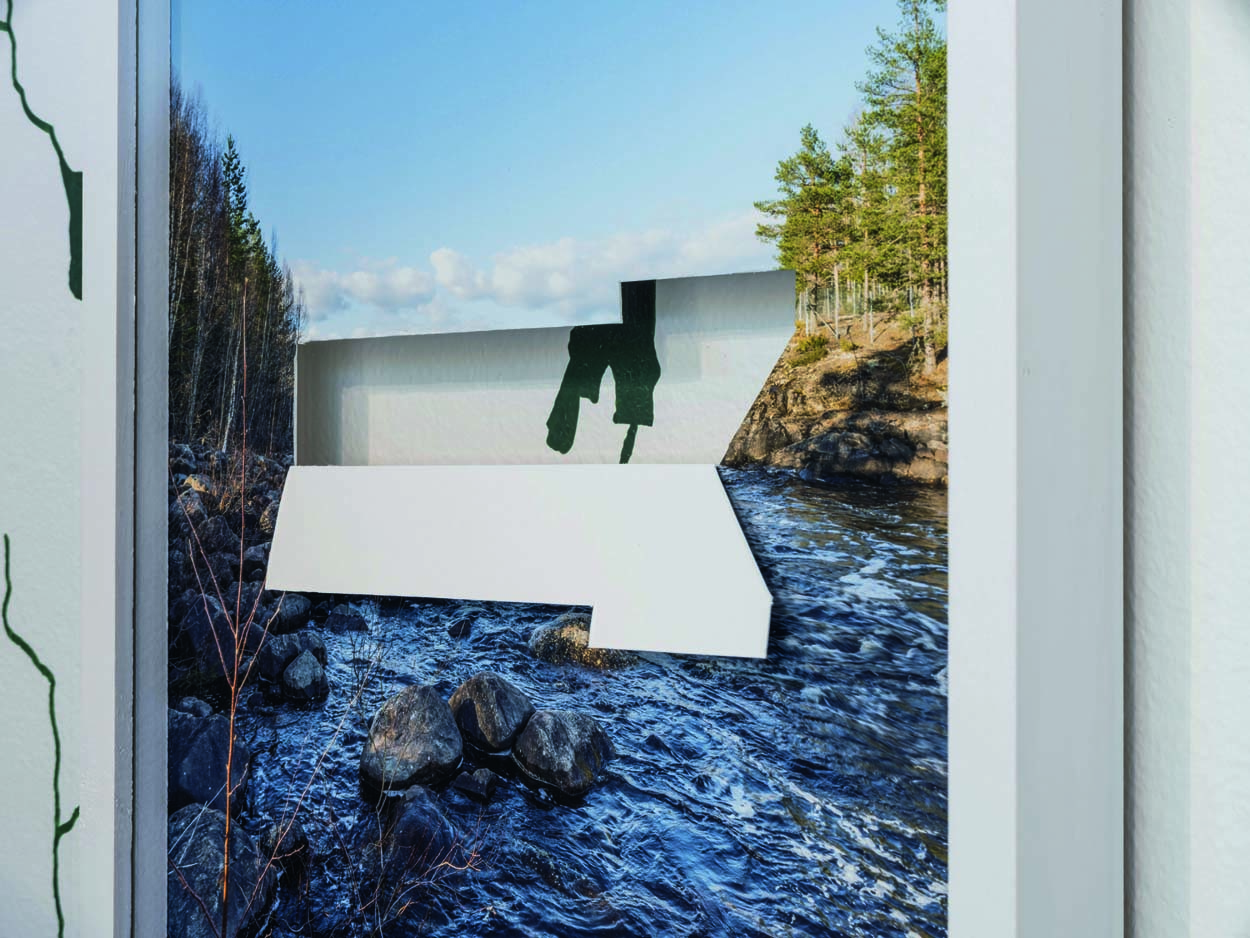

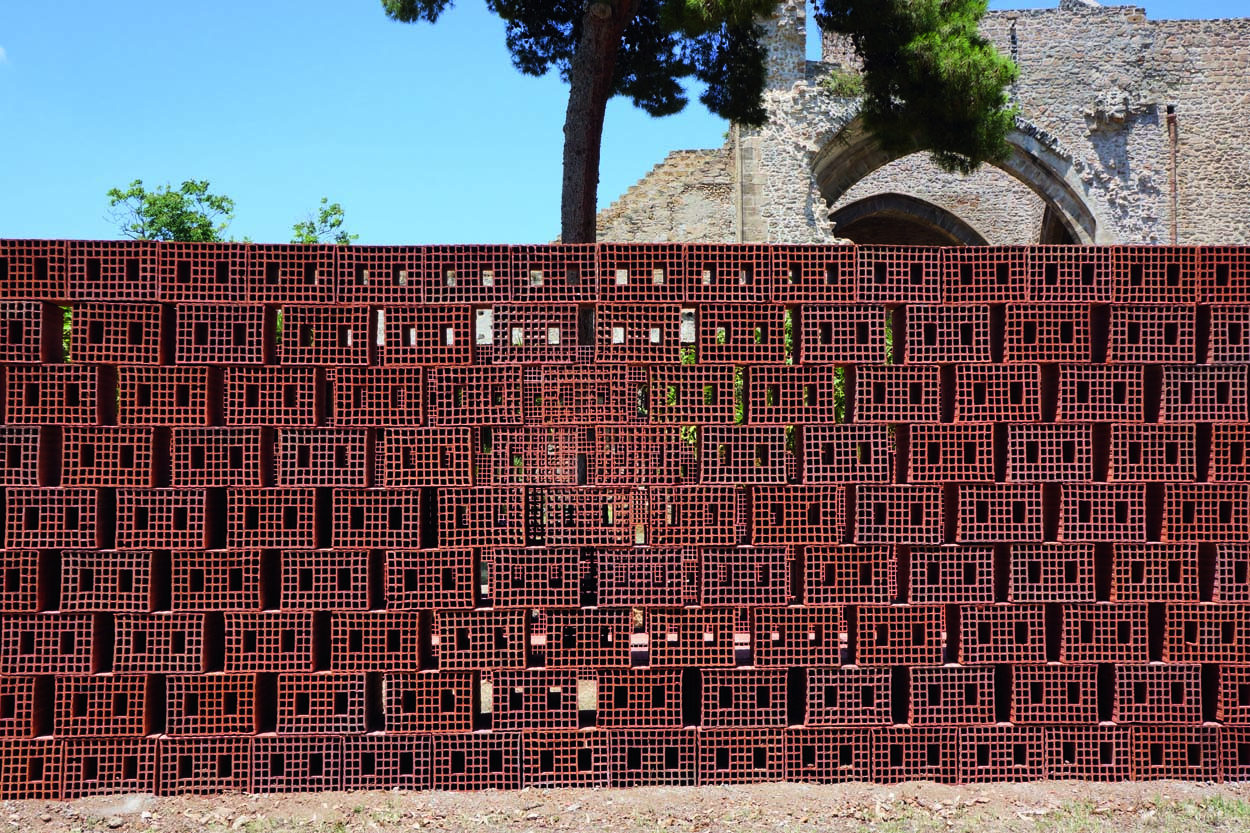

Artist duo Cooking Sections’ work combines art and activism, using food as a gateway to explore the social, cultural and political drivers of the climate crisis. Founded in 2012 by Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, Cooking Sections incorporates design, architecture and community work to create works that defy simple categorization. In their multi-site project CLIMAVORE, they examine how climate change has eliminated traditional seasons, instead identifying the new ‘seasons’ of the climate crises: periods of drought, oceanic pollution and soil depletion. Yet their work also explores potential solutions, looking at how we can create adaptive and regenerative forms of food production. Thus, rather than just working with temporary installations, their practice actively seeks to create frameworks that can be continued in a local context after an exhibition is over. This incorporated solution aspect offers a much-needed glimmer of optimism in a struggle where many of us can find ourselves feeling powerless. Their work is not about the individual choices we make, but about facing the structural issues that are accelerating the climate emergency, and encourage us to demand change by those in power.

Cooking Sections: It’s a term we coined in 2015 to think of different systems and how to use food to understand them. We use food to understand those systems and how they are adapting to the new seasons of the climate crisis. It starts from the idea that the seasons that we grew up with have become or are becoming more and more obsolete. For example, when you go to the supermarket, you find pretty much anything all year round because of these standardized and intensive ways of producing food. So we started thinking about what it would mean to eat according to the new seasons that are being generated by humans because of the industrialization of the world. Like a season of drought or a season of polluted oceans or a season of flash floods. And that’s when we started thinking of these possible ingredients, variations that on the one hand are becoming more common in places they were not before, but at the same time also possible scenarios we can imagine to address them.

“Too often, the responsibility of a malfunctioning of a system is put on people’s individual habits instead of thinking more systemically.”

CS: Well, I think for us, more than the convivial aspect – which is also important for us – it is more about how to think of food as an infrastructure, especially thinking about systemic change at the levels of governance as well as policy-making and how to bring different allies into these struggles towards food justice. And to do that, we like to operate at different levels. Of course, people get together to eat and it’s very important. But even if that sometimes becomes part of our work, the focus is more on infrastructural change that doesn’t stay at the level of the individual. Too often, the responsibility of a malfunctioning of a system is put on people’s individual habits instead of thinking more systemically. For example, why are food corporations allowed to use certain pesticides and then make people pay three times more in the supermarket for food that doesn’t have those chemicals or poison? We want to put more emphasis on those layers, not only on the conviviality of people getting together and eating nice food.

CS: It has also been made polarized, right? People grew up with it for centuries and it was something very embedded in everyday life. But because of the industrialization of food, especially after the Second World War, more and more people have become disconnected from food and food has become more disconnected from landscapes and the natural seasons because of different so-called technological modernizations. But that has also created a whole series of problems. And that’s where we think this divide appeared. It has become really politicized and, actually, should be even more politicized because it’s a real struggle. Food production is now driven by corporate profit, like many other extractive industries in the world. There is that gap that needs to be bridged. And it’s not easy.

CS: For us, it’s important to use cultural platforms to, on the one hand, raise awareness about these connections, while it is also very important to imagine a new, possible future. We need to start thinking about how we can end some of these extractive practices or toxic ways of farming. And to do that, we need to imagine better worlds. Which is what we try to do in our work, to pick some of these cases or stories from our research and then amplify them. For instance, one particular case is the whole body of work around farmed salmon and the synthetic colors that are used to pigment the flesh of the fish. The fish are grown in intensive farms underwater and because of deficiencies in their industrialized diet, their flesh doesn’t turn pink, the way people expect them to look. So, artificial coloring is used to compensate for it. In this particular case, we use the illusion of color to expose and reveal how the production of farmed fish creates serious new problems. It is not just an aesthetic problem in terms of color, but that fake color that is illustrative of the problem with the entire system.

“In order to make food affordable and to feed the world, some of these very intensive and toxic practices have been heavily subsidized by governments without thinking of the long-term future of the soil or the long-term future of our bodies.”

CS: Definitely. But we first need to understand that we’ve been forced to disconnect. Because people were not disconnected that long ago. We need to think of the externalities. In order to make food affordable and to feed the world, some of these very intensive and toxic practices have been heavily subsidized by governments without thinking of the long-term future of the soil or the long-term future of our bodies. [Our bodies] are becoming increasingly infertile because of exposure to some of the pesticides that are used in to lower the costs of the production of food. So, at what cost does cheap food actually come, at what cost to the environment, at what cost to our bodies? At the moment, cheap food is cheap because of these subsidies to corporate profit-oriented enterprises, but also because it doesn’t take into account the long-term effects and who is doing what with those externalities. If you were to include the price of cleaning the waterways from pesticides, would it be that cheap then? The problem is that those costs are not included in the price of food. For us, it’s about making these connections visible. It’s not people deciding to disconnect from food, it is enterprises that have been severing those connections.

CS: Yes, of course. There are a lot of farmers that are doing incredible work in many parts of the world, who try to resist those corporate structures and still take care of the land and the soil for future generations. And there’s a lot of initiatives. I think the problem sometimes is that they feel that society demands a lot from them in terms of ecology, but no one is really supporting them in the way that some of these more industrialized food production systems are subsidized. So, on the one hand, they have to bear the risks of failure because sometimes the weather doesn’t help, especially if you don’t use chemicals to mitigate. And, on the other hand, it’s a social responsibility they feel that people demand from them. That is a huge psychological load to carry. There needs to be more support for long-term visions and for food production that takes care of both humans and the soil.

CS: Demanding more infrastructural change. Governments should support, for instance, open source seeds without copyright or patents by multinational corporations so that farmers don’t need to pay for seeds that are climate resilient. We need to have open source seeds for farmers so they can decide on their future and what they want to grow without paying because that’s how humanity has always been. Another infrastructural change we need to demand from government: Think of when we go to the supermarket. We are put in a personal quandary and a financial bind, where we have to choose if we want to pay three times more not to be poisoned, instead of the government just banning these pesticides from the start. These kinds of choices are then up to people’s habits and the information they have instead of governments and corporations taking the responsibility.

CS: Exactly.

CS: It’s hard to say… We just believe in the work we are interested in and it doesn’t have to do with being more or less common. We love allies. We’d like to have more allies and people do it more at work. But yeah, there are many issues in the world and each one focuses inwards.

CS: We’ve been working a lot within the climate framework and thinking about the future seasons. For instance, in a season of drought and there is a lack of water or water scarcity, let’s think of more drought-resistant crops. Or if there is a season of soil exhaustion because so many chemicals have been applied that the soil is dead, what kinds of rotation of crops can nourish the soil in the same way that we nourish our bodies? These are the kinds of ingredients we try to find, but we also look at ways of growing them that support ecological systems, not just addressing the ingredients themselves.

CS: We need to familiarize ourselves with the local plants that are available. For example, in the south of Italy, there are all of these wild plants, nut trees and varieties of vegetables that don’t require irrigation. So, on the one hand, familiarize ourselves with them, and then create a demand.

CS: Again, that depends on where you live and where you are. For example, on the Isle of Skye in Scotland, where we did the project on farmed salmon, we’ve been working a lot with alternative aquaculture, mainly oysters, mussels and seaweeds that contribute to oxygenated water as they grow. Seaweed, for instance, is an ingredient that in Scotland had been used for generations but has been forgotten, especially since industrialized food production started after the Second World War. We look at how to recover some of these cultural legacies for the sake of history, but also as foods for the future. They are incredible sources of protein and many other compounds that our bodies need, but have been disregarded. So, it is crucial to reconnect with these ingredients, but it all depends on where you live and what the main issue at stake is. For example, if you live on the coast and you have fish farms nearby, how can you transition to alternative aquaculture? If you’re in an area that is experiencing increasing drought, how can you grow vegetables that do not require irrigation? And so on.

CS: What we can do is to ask questions, ask yourself why is this available? Why is this not available? It’s a lot about information and talking to people and thinking. For example, if you are in a dry environment affected by drought, look at why there are not so many ingredients that respond to drought. Because the moment you start pulling the thread and tracing it, then you understand all the actors that are involved, and then you can demand change. It’s not easy to do it on an individual level. But, we have to because it’s our everyday life and we need to constantly make good choices. And there is a lot of work to be done on a wider, infrastructure level.

Sometimes, says Italian philosopher and author Emanuele Coccia, we forget that for a long…

It’s one of Berlin’s event highlights of the year – the Half Marathon. But even…

UGG® has teamed up with Los Angeles-based designer and multidisciplinary artist Reese…