Supercontinent “fashion”: Numéro Berlin in conversation with Emanuele Coccia

Sometimes, says Italian philosopher and author Emanuele Coccia, we forget that for a long…

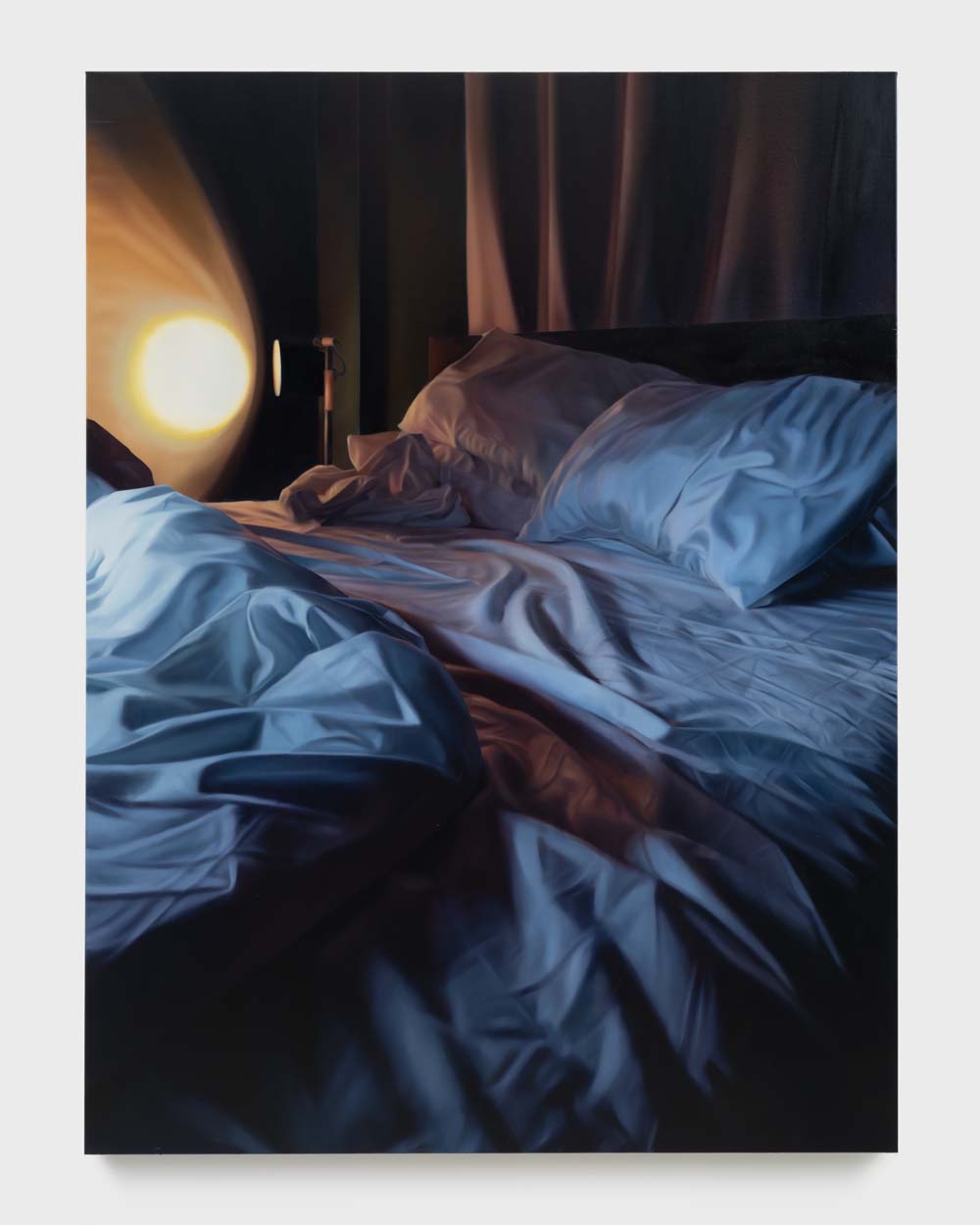

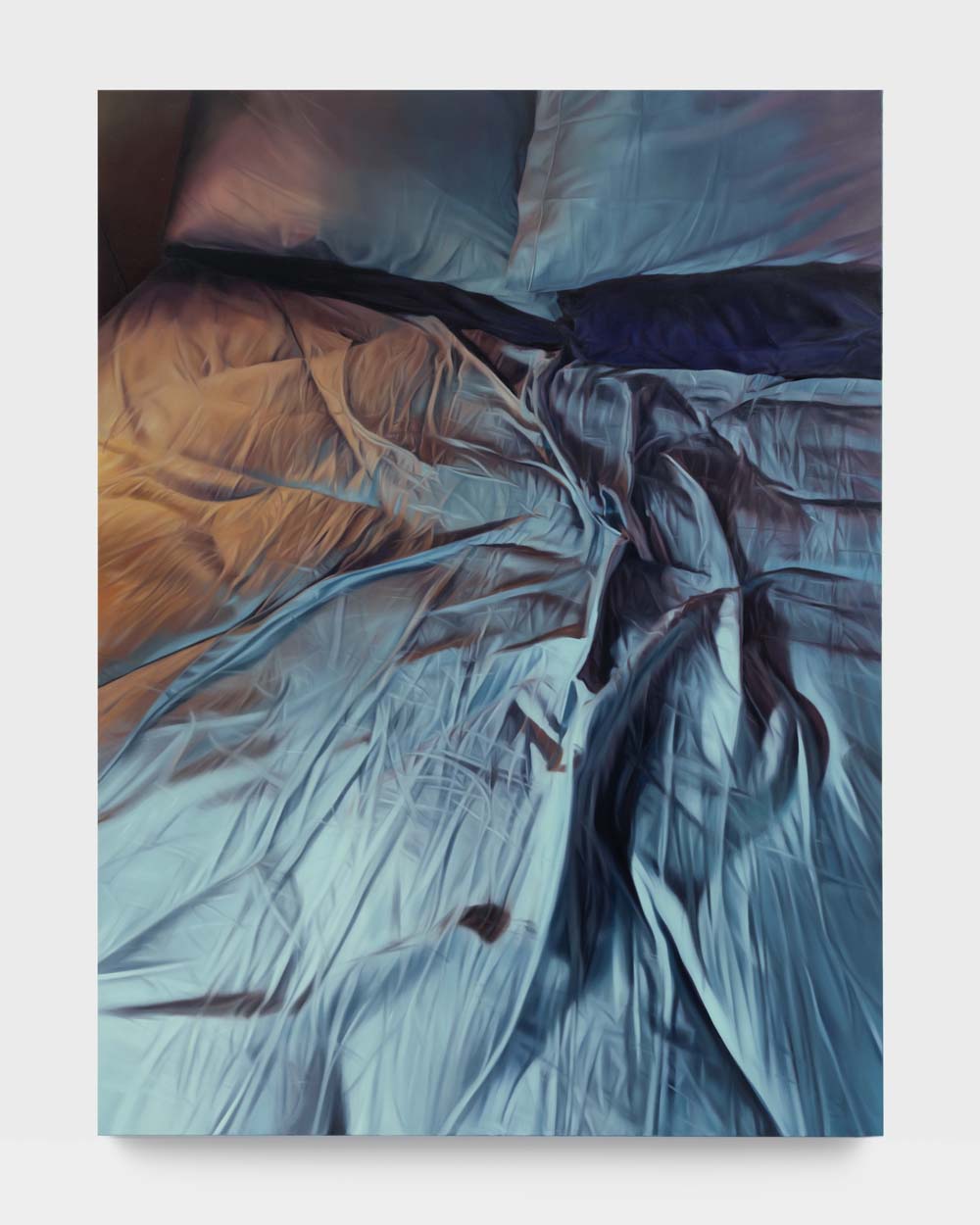

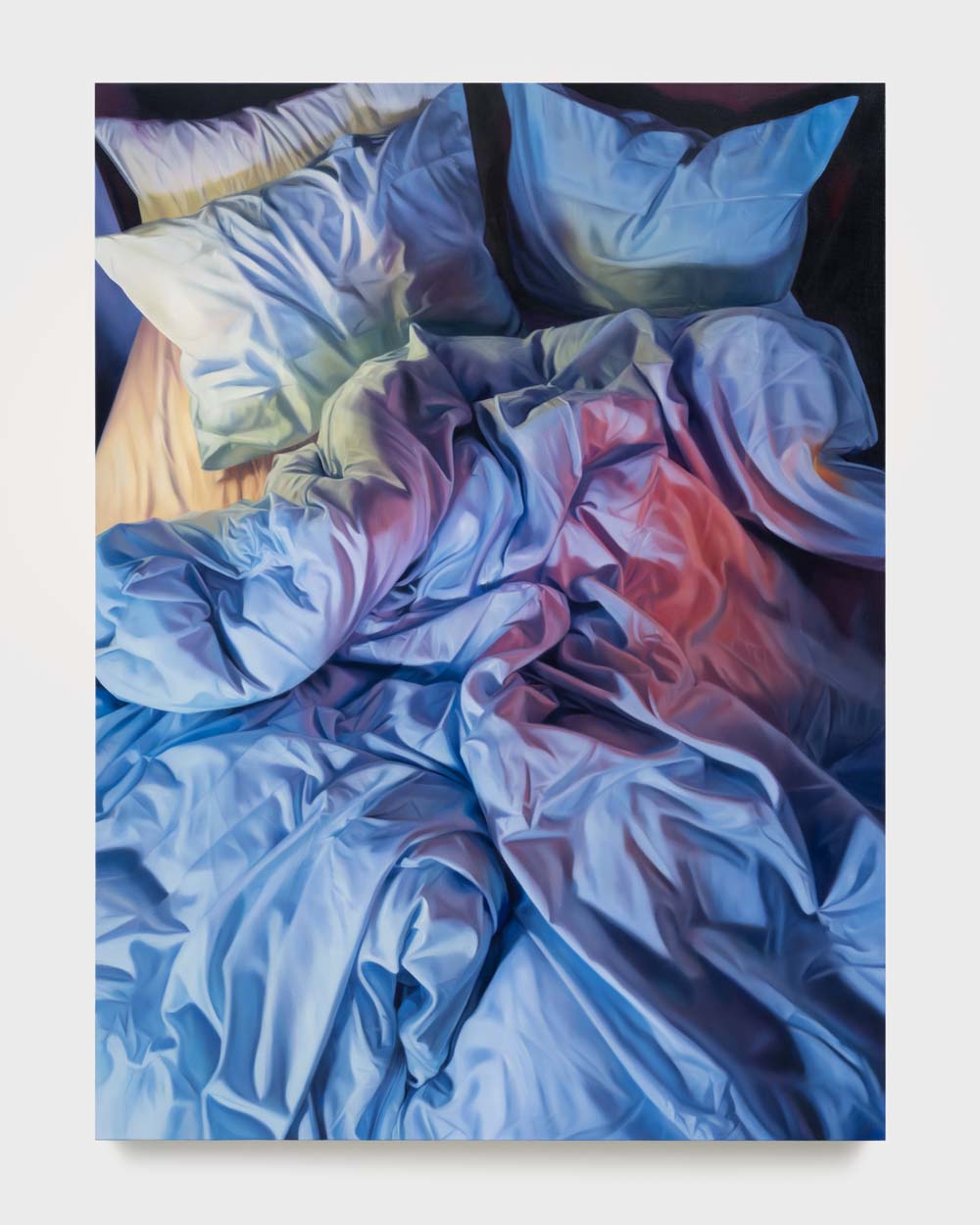

“Just because a bed is empty, doesn’t mean it can’t be filled with longing.”

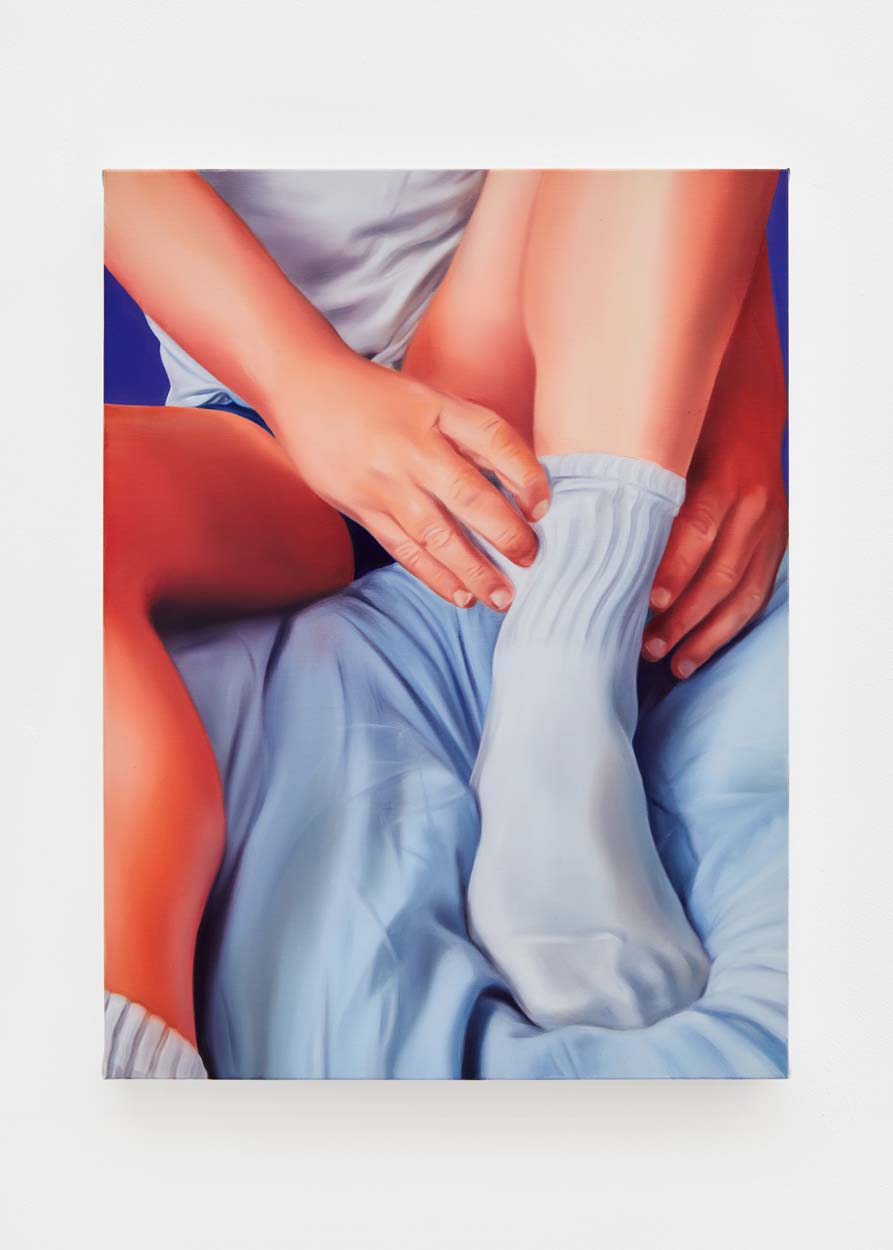

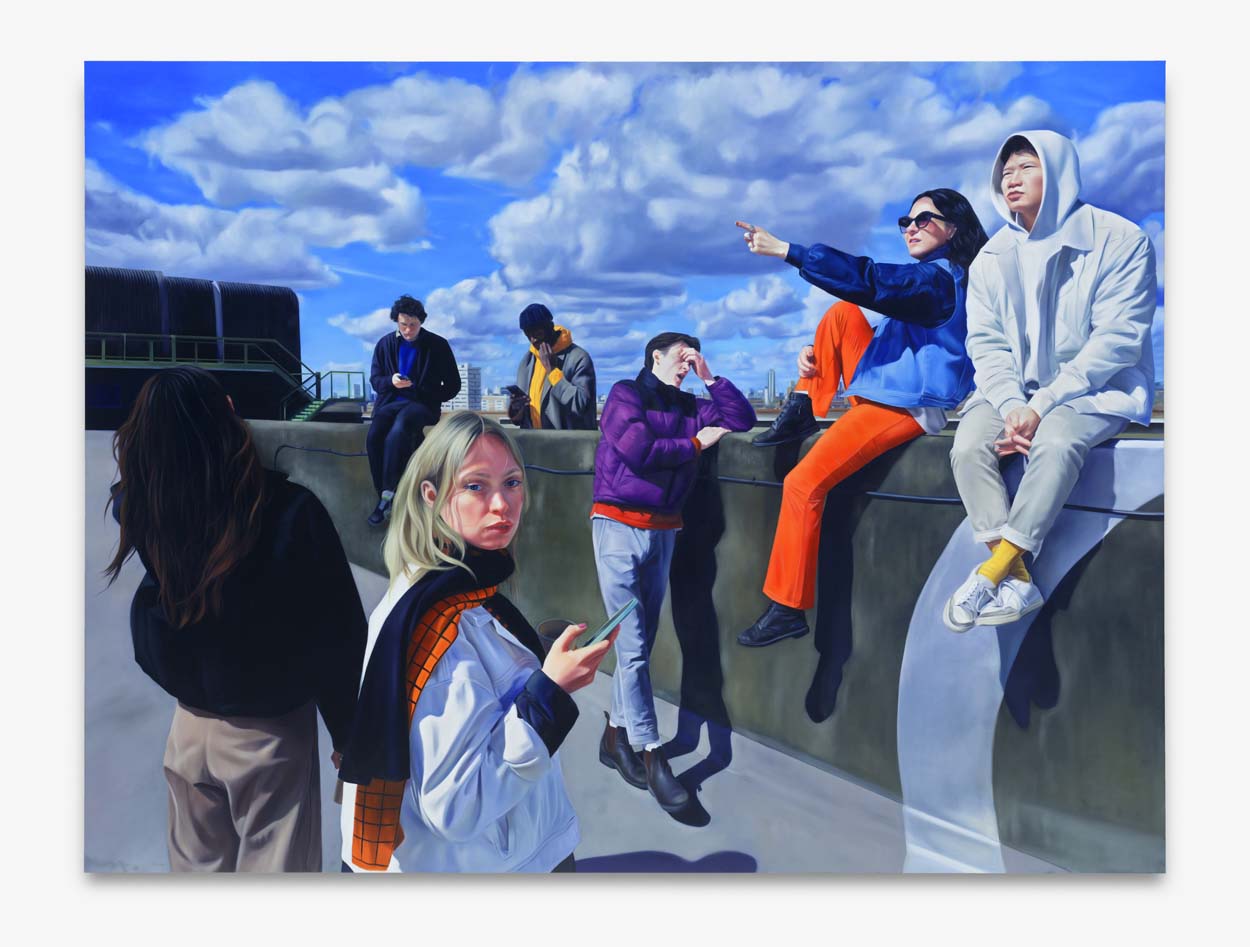

The creased and draped linens in Christopher Hartmann’s most recent show at Blum and Poe Gallery in Los Angeles use human imprints rather than the figures themselves to tell stories and play with the idea of opposites. The 30-year-old artist dives into domestic messes, using piles of clothes like a Rorschach test and celebrating the joy of four white socks peeking out from under a duvet. Catching up with the artist on his way back to London, Hartmann speaks on longing, belonging and growing into subtlety.

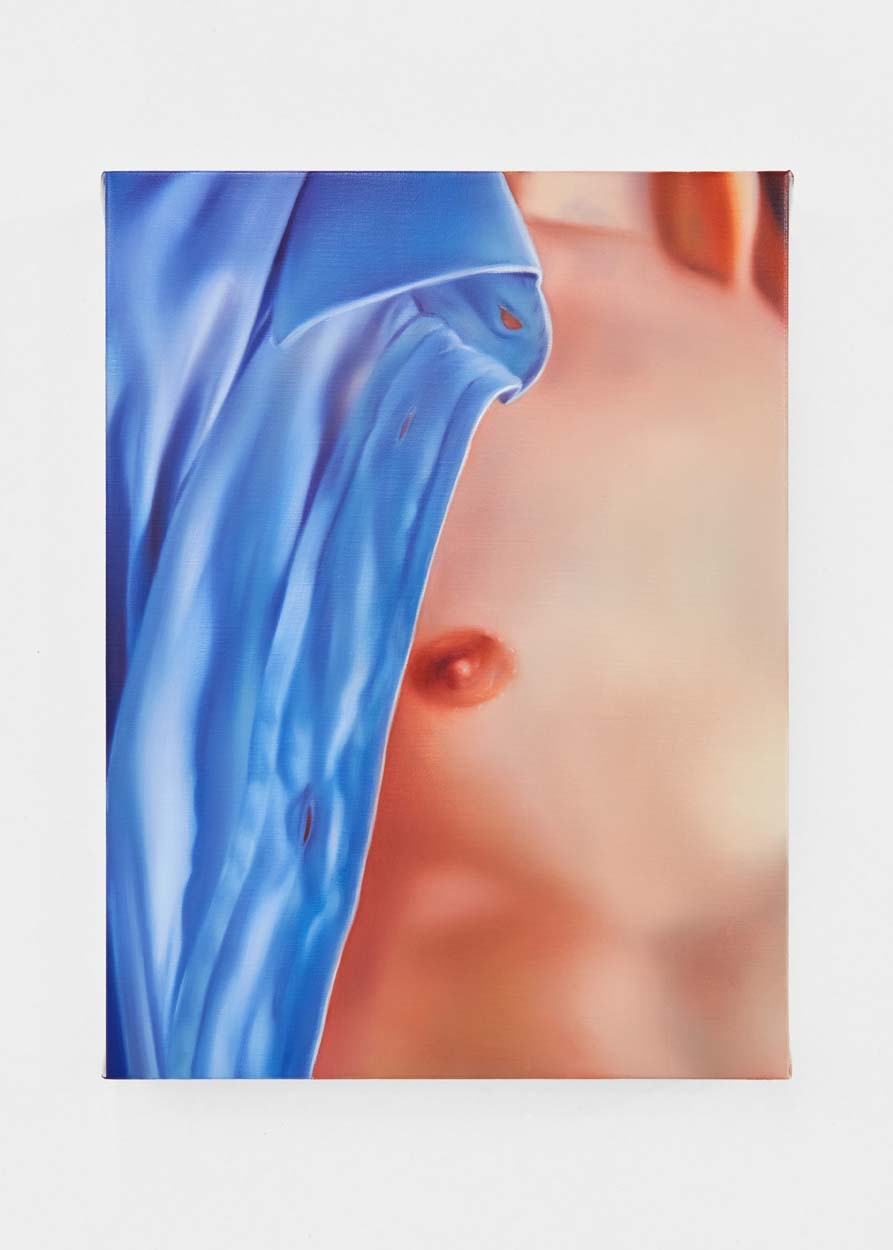

Christopher Hartmann: The initial starting point was the first lockdown in 2020. My previous work was very figure-heavy, about flesh and skin. All my work is staged to a certain degree, I take photographs before I paint. During the lockdown, I wasn’t able or allowed to take images of people, that’s when I became more interested in clothes and suggesting a certain presence through the absence of figures. I was staring at a pile of clothes at home and noticed the movement of the fabrics and impression of the body.

The first room in my exhibition is just empty bed sheets, empty beds — what I am most interested in is the absence of the body, to suggest with an imprint of a body that a body was there. With the fabrics, it creates a different type or relationship between the paintings and the viewer. Through the fabrics and textiles, the viewer can interpret the motif I am portraying through their own experience.

I am a controlled messy person. Not to reinforce stereotypes, but I’m a typical Capricorn, and on top of that I am German — always in control. My studio can get messy sometimes, but I have it under control. At a certain point, I have to clean. I also don’t mind mess, as long as it is my mess and I have some kind of overview of it, but if it is somebody else’s mess, I do get a bit crazy about it.

The pile of clothes I paint are very staged and composed – I spend hours on them. Some of my scenes are more natural states, but they exist in a place between staged and natural. Very often, a still life starts with me seeing something on the floor or on the couch. I then take a few pictures and start to remove or add something to make an interesting composition. I am aware that the end goal is painting.

As a man, it feels like the most authentic thing I can do: paint men and show things from my perspective. If you had asked me three or four years ago, I would have told you that my work is a reflection of my belief that there aren’t any fixed ideas of masculinity, but in 2023, I don’t think so much about gender norms.

There is a certain vulnerability and tenderness to the paintings, which is in contrast to a traditional sense of masculinity — but it’s not a groundbreaking new idea. For me, tenderness, vulnerability and masculinity go hand in hand. These aspects are intrinsically human, regardless of gender, sex or whatever. It is the way I am and how I relate to people in my life.

“I had just moved into a new flat in London and the starting point of that was me just staring into an empty bed. The idea of starting over was heartbreaking.”

Obviously, I can’t separate myself from my environment. I grew up in Bavaria, in an ultra-Catholic environment, so I am aware of the traditional view of masculinity. But maybe it is tied to leaving home. Sometimes I wonder if I am in a bubble, living in London, in the art world, thinking that people are very openminded and less fixated on certain ideas.

Five years ago, I was pushing ideas of sexuality and masculinity. But now, my work has become a bit more supple and tender. Maybe this also has to do with age. There is something about the subtleness that I find more interesting, showing more, but being less explicit.

My most recent work in LA was about longing and belonging and exploring the idea of home. I had just moved into a new flat in London and the starting point of that was me just staring into an empty bed. The idea of starting over was heartbreaking. I was staring at the bed and thinking about where you sleep at night and where you define your home.

Now, I am much more interested in abstraction. Instead of painting a person who looks nostalgic or painting a fleshy intimate scene, I am interested in depicting atmospheres that express nostalgia or show an intimate state of mind.

I am interested in that duality — absence points towards a presence and a presence points towards an absence. Each provokes something different in the viewer. You can very much relate to an empty bed, and it can be very confronting, but two figures are much more explicit, much more specific, and about interpretations of the poses and action. But I like telling stories across this juxtaposition.

Sometimes, says Italian philosopher and author Emanuele Coccia, we forget that for a long…

It’s one of Berlin’s event highlights of the year – the Half Marathon. But even…

UGG® has teamed up with Los Angeles-based designer and multidisciplinary artist Reese…