#GLÜCK: CHAPTER I

Photography by Rita Lino

Sometimes, says Italian philosopher and author Emanuele Coccia, we forget that for a long time, garments were made out of animal skin. For centuries, fashion meant putting oneself under the skin of another life form. If debated correctly, could fashion become an instrument to shape our future, reinventing our relationship with each other, nature, and freedom, serving as a global, planetary language?

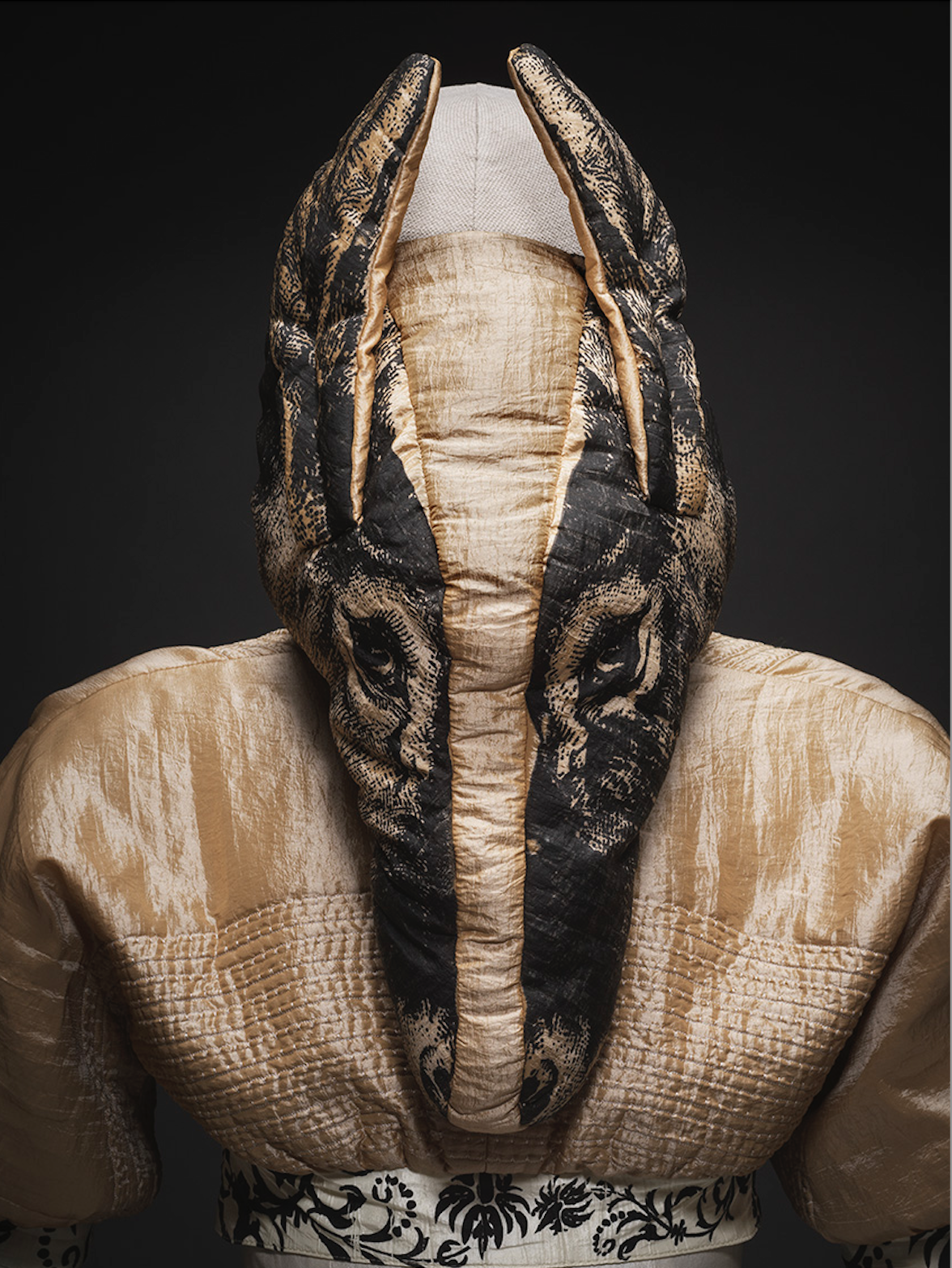

As part of the International Talent Support initiative ITS contest, philosopher Emanuele Coccia and fashion curator and expert Olivier Saillard have curated a second exhibition titled ‘Fashionlands – Clothes Beyond Borders’, which is now open in Trieste for the next 10 months. The show explores the changing boundaries of fashion and its role in contemporary society, as well as the power of experimental creations in comparison to the symbolic value of everyday clothing. Questioning the concept of dressing and creative freedom, the duo selected works by 23 designers from the permanent collection of ITS Arcademy, supported by beautiful still life photographs from Gabriele Rosati, capturing the functional and timeless nature of clothes that can transcend the idea of classes and luxury. A public choice award will reward the designer receiving the most votes from visitors throughout the 10 months – the winner will receive a €5,000 prize in January 2026.

The ITS Contest, which celebrated its 20th anniversary in 2022 and has significantly contributed to the careers of contemporary creative directors and designers such as Matthieu Blazy, Demna Gvasalia, and Richard Quinn, is an integral part of a unique ecosystem, complemented by ITS Arcademy – Museum of Art in Fashion, the first and only contemporary fashion museum in Italy. For this year’s contest, Barbara Franchin, President of Fondazione ITS and founder of ITS Contest, in collaboration with an international jury, has selected 10 young finalists from China, the UK, Belgium, Germany, and France, all of whom showed a new, liberating, and refreshing perspective on fashion. “Offering all designers the opportunity to grow together is a new answer to the global and ethical challenges of our time. Focusing on collaboration instead of competition was the most responsible choice to enhance the potential of this new generation of designers,” says Franchin. “The main challenge for designers and fashion is to be able to value things and nurture the idea of material values,” says Serge Carreira, Director of the Emerging Brands Initiative at the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode and a member of the ITS contest jury, in a conversation with Numéro Berlin. “What is interesting is that most of the projects selected this year also focused on innovation in the creative process as well as in the making process and craftsmanship. Luxury is a matter of excellence, not price.”

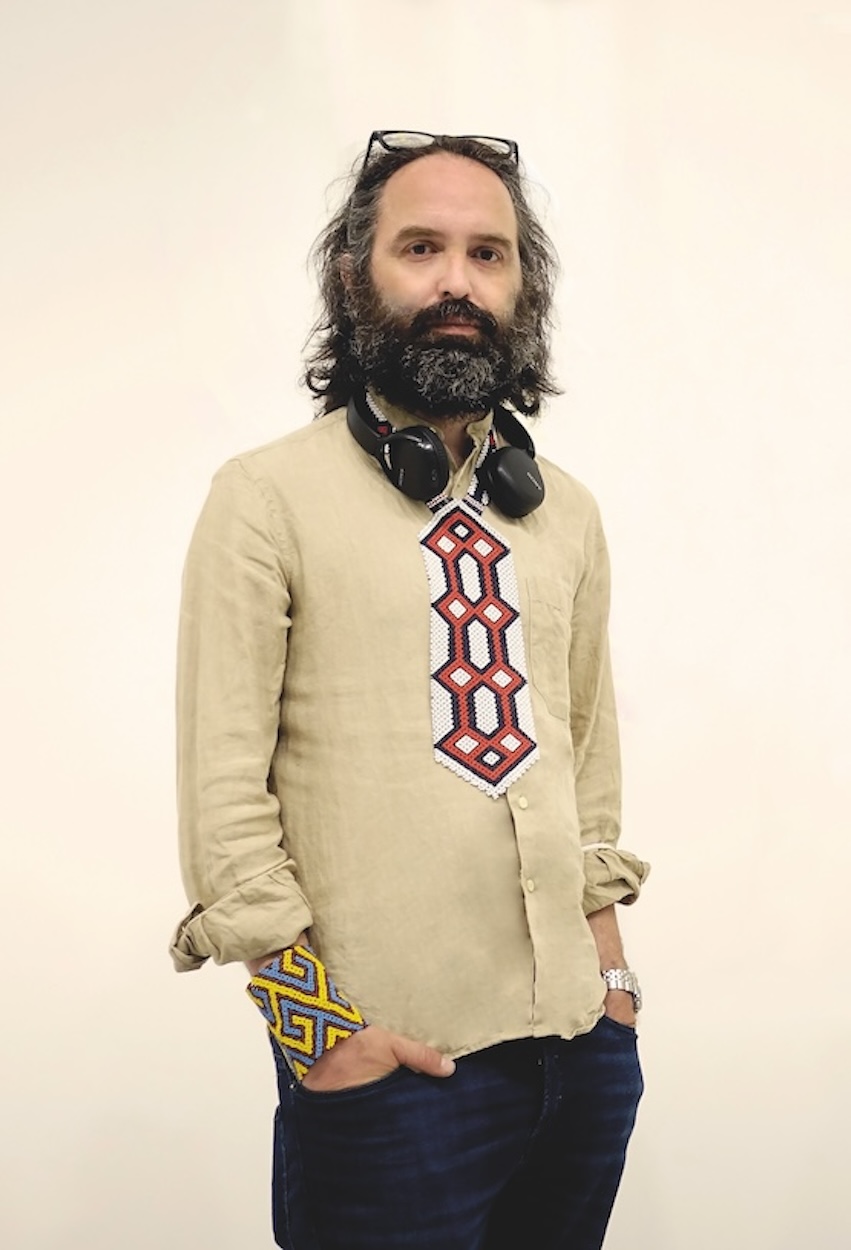

Numéro Berlin spoke to philosopher Emanuele Coccia about why the industry’s issue is, above all, a lack of proper debates. This week, his and Alessandro Michele’s new book “Das Leben der Formen” will launch in Germany. Before traveling to Munich, we caught up with him at the ITS Arcademy during the inauguration days of the ITS contest.

Emanuele Coccia: It’s the second exhibition Olivier and I are doing. In this case, the theme was extremely clear. The overall intention was to produce a sort of new cartography of fashion to explore, on one side, how fashion invented and created a new language that is globally and planetary relevant. Unlike many other artistic artifacts, fashion produces objects that are perfectly readable and understandable from Beijing to Los Angeles, from Dakar to Sydney, from Paris to Buenos Aires. Of course, the process of becoming planetary has gone through violent and problematic phases, but it’s clear now that this is not something accessory to fashion because, in a way, fashion is the exercise of adding something new to your body or mixing your anatomical identity with something completely exterior. Some pieces are recognized as more intimate than your own body. It’s always this exercise of trespassing the border of your skin, and because of that, no other border becomes relevant.

Emanuele Coccia: It’s the second exhibition Olivier and I are doing. In this case, the theme was extremely clear. The overall intention was to produce a sort of new cartography of fashion to explore, on one side, how fashion invented and created a new language that is globally and planetary relevant. Unlike many other artistic artifacts, fashion produces objects that are perfectly readable and understandable from Beijing to Los Angeles, from Dakar to Sydney, from Paris to Buenos Aires. Of course, the process of becoming planetary has gone through violent and problematic phases, but it’s clear now that this is not something accessory to fashion because, in a way, fashion is the exercise of adding something new to your body or mixing your anatomical identity with something completely exterior. Some pieces are recognized as more intimate than your own body. It’s always this exercise of trespassing the border of your skin, and because of that, no other border becomes relevant.

What was interesting for us was to show how a kind of artificial universality is produced because, in a way, unlike other representations, universality in fashion is always produced by sewing elements together or by composing different memories, traditions, and nationalities. With our selection, we wanted to show garments that embody or unify different memories, traditions, genders, and silhouettes. That was the criterion for the choice of objects. It was extremely important for us to stress that, for fashion, every identity is a mixture or hybrid of different identities. There is no pure identity.

Yes, this was the second element. We wanted a young photographer who excels in still lifes of garments without human beings. The point was to grasp those basic forms that fashion has invented, like jeans, t-shirts, gloves, trench coats, etc., which are also universal in the sense that they are used by both the wealthy and non-wealthy, by every gender, and by every designer. In a way, they are forms available to everybody, but they are already meaningful or significant. The trench coat expresses a sort of urban mystery but can also signify much more. Items such as trench coats are basic elements of the universal language of fashion, and Gabriele was extremely talented in understanding this idea. He managed to express the almost Platonic essence of each garment. The choice of black and white emphasized this idea, depicting the garments as something anonymous. We see these forms every day, but they are becoming almost invisible; Gabriele made these forms in their strangeness visible again.

First of all, in a way, fashion is the only medium capable of crossing the limits of time. You cannot paint like we did in the 20s; it would be considered kitsch if you tried. In fashion, you can genuinely take past events and reinterpret them, liberating the past from its original context. You give these forms a new power to disrupt the present. It’s very strange since the chemical treatment of time allows us—through fashion—to escape from our life, both from the past and present.

Yes. There are many good examples; for instance, when Yves Saint Laurent in the 70s started using forms and styles from the 40s, it wasn’t an assertion that we should return to the 40s; rather, during the 40s, women were particularly powerful—men were off to war, so women were in control of the city. His idea was to use these forms to embody empowerment for women. The treatment of time and this characteristic of being borderless—not just in spatial terms but also in temporal dimensions—gives fashion incredible power. No other art form has this capacity. Of course, paintings, sculptures, and architecture are all practices that offer us freedom, but fashion grants us freedom every single day, in a public form, for every single body, because everyone is meant to be dressed.

Sometimes we forget that for a long time, garments were made from animal skin; thus, having a garment meant, for centuries, putting oneself under the skin of another life form. From this perspective, there are potentials that could allow fashion to reinvent our relationship with nature. Even among this year’s finalists, there are at least three projects truly focusing on this aspect. I believe it’s an issue that more and more young designers are considering in their work. I think that because of fashion’s universality—being an inescapable art, everyone must pass through it—fashion holds a vast potential for renewing our relationship with other life forms and allowing us to understand what it means to be under the skin of another.

This is actually something fashion radically engaged with in the 50s and 60s: when haute couture brands decided to open ready-to-wear lines, it marked the final divorce from the notion of fashion as an instrument of distinction, a class, or proof of economic and social superiority. There is a stylistic line that transcends all classes, so what fashion must do is not distinguish classes but capture the spirit of the time. That was the main idea and what granted fashion its enormous democratic potential. However, unfortunately, in the last decade—let’s say the past 20 years—a lot of companies have tried to revert to the idea of fashion as luxury, which is exactly the opposite, limiting access to very few people. This is an extremely conservative and reactionary idea. Luxury is not fashion. Fashion can, of course, embrace and include luxury, but luxury is not necessarily fashion. What those groups are doing together is extremely dangerous because it’s not just about economic politics; it’s an attempt to kill the spirit of what fashion is.

Let’s start with this institute here. It is so important because it does not follow the same model as other competitions like ANDAM, LVMH, or even HYRÈS, which tend to select candidates who share the same core profile as those at the helm of big companies. Here—you saw the candidates this year—you can find much more diversity. Some candidates do not produce with the intention of entering the industry. They create passionately and in a very diverse manner. This is also happening on different scales in different countries, in the sense that many students coming from fashion schools do not want to work in these large industries. They are trying to invent new commercial networks where, for instance, their creations are sold in art galleries, rather than in this huge retail system. So, that is one aspect. Another is that perhaps we should discuss new generations more—magazines shouldn’t solely focus on big names, but on the fashion produced by every single human being. We should really extend the discourse around fashion.

Yes, we finally need to integrate fashion into education at schools. Fashion is the only art that is not significantly taught at schools or universities, unless specified. Every person studying human and social sciences is expected to know a bit about the history of painting, sculpture, and architecture, but society tolerates ignorance regarding the history of fashion. This is also a fault of the big brands because, in a way, they are responsible for the lack of discourse surrounding fashion. They do not produce interesting discursive elements such as art galleries or books; they do not encourage people to write essays on their products. In essence, fashion companies are never interested in discourse; they assume that consumers who buy fashion are entirely illiterate. Just to give you an example, the fact that Miuccia Prada opened the foundation in Milan and showcased everything but never garments evidences their belief that fashion is simply business and not art. Otherwise, they would have displayed some of it.

Of course. If you promote and push certain values, then everyone will resist attempts to identify fashion with luxury. This ignorance also impedes people from appropriating fashion. That’s why it is also their responsibility. It is a crime that Chanel or other big companies like Balenciaga do not open their archives. Coco Chanel, it is evident, advanced humanity; she liberated many women. How can it be that the owners of this heritage hide it in the suburbs of Paris, believing they cannot show it for fear of being copied? It is such a ridiculous and irresponsible attitude from a cultural standpoint. These companies should finally recognize that they have cultural responsibilities to the global population, not just to the cities where they are based.

Yes, it is a very strange strategy, even from a commercial viewpoint. It’s clear that no one will ever possess the force and genius to create like Alexander McQueen. It would have been far better to take that money and invest it in some young designers rather than trying to produce a cult around a deceased person, which is purely necrophilia. It’s not just about countries; it’s also a major mistake from an economic perspective. Some of our past great designers were so significant—they contributed immensely to the globalization of fashion and initially had very strong successors, like Galliano, for example. But then, at a certain point, they became extremely reactionary. They are genuinely trying to kill fashion at the moment.

We’re completely lost, and the system will likely break down. You can welcome a designer but don’t expect them to dream the dreams of someone else. There are many new designers from China who do not encounter these cumbersome problems and focus more on genuinely innovative design. Those groups should operate more like art galleries.

Well, they could do that very quickly if they wanted.

Yes, but artificial intelligence is not an automatic instrument. When everyone uses artificial intelligence, the results become homogenized. It is a tool that cannot replace creativity, invention, and imagination. It allows us to go faster and create more, but we will always need people behind those instruments—in the same way that computers did not eliminate the need for someone to operate them to choose, decide what to do, or design what to wear. This is something special to fashion; we truly need to like the pieces we wear. One must, in any case, reinvent styles and reclaim one’s own freedom.

I would actually like to enter the industry to change the landscape a bit. It’s not easy, but there is significant resistance to culture in general. I’m working with the Fondation Cartier in Paris, trying to develop spaces where fashion can be discussed. It’s absurd that there’s no venue in either Paris or New York where fashion could be debated.

Photography by Rita Lino

Gucci unveils The Art of Silk, a project that celebrates the brand’s heritage in silk…

It’s one of Berlin’s event highlights of the year – the Half Marathon. But even…